Optimizing Polycystic Ovarian Disorder (PCOD) Treatment with Personalized Lifestyle and Nutrition Strategies

Most Sufia Begum1*, Samira Areen2

1Professor (cc), Delta Medical College, Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Assistant Professor (cc), Delta Medical College, Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh

*Correspondence author: Most Sufia Begum, Professor (cc), Delta Medical College, Mirpur, Dhaka; Email: tito64016@yahoo.com

Citation: Begum MS, et al. Optimizing Polycystic Ovarian Disorder (PCOD) Treatment with Personalized Lifestyle and Nutrition Strategies. Jour Clin Med Res. 2023;4(3):1-8.

Copyright© 2023 by Begum MS, et al. All rights reserved. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

| Received 04 Oct, 2023 | Accepted 18 Oct, 2023 | Published 25 Oct, 2023 |

Abstract

Introduction: Polycystic Ovarian Disorder (PCOD) is a prevalent endocrine illness in women of reproductive age. It has hormonal abnormalities, irregular menstrual cycles and tiny ovarian cysts. Lifestyle and food affect PCOD development and maintenance, coupled with medical therapies. Lifestyle, diet and PCOD are interconnected in this thorough assessment.

Methodology: The evaluation comprises PCOD, lifestyle, diet, exercise, stress management and nutrition research published between January 1, 2000 and May 1, 2023.

Result: PCOS management requires lifestyle changes including frequent exercise, a healthy weight, nutritious diet and no cigarettes. While lifestyle modifications cannot substitute medical care, they improve well-being. Low-GI, ketogenic and omega-3 fatty acid diets may reduce insulin resistance and PCOS symptoms. Eating no Saturated Fats (SFAs) is also important. Exercise improves insulin sensitivity, but high-intensity sessions improve cardiorespiratory fitness, insulin resistance and body composition more. We propose intense aerobic and strength training. PCOS might worsen insulin resistance due to sleep disruptions. Getting enough sleep is important for metabolism. PCOS sufferers may have reduced melatonin, which regulates the body’s 24-hour schedule, underlining the significance of sleep. Vitamin D, inositol, folate, B-group vitamins, vitamin K and vitamin E may improve insulin sensitivity and hormonal balance. Vitamins including bioflavonoids, carnitine and alpha-lipoic acid and minerals like chromium picolinate, calcium, magnesium, selenium and zinc may also help PCOS sufferers. More study is required to prove their effectiveness.

Conclusion: PCOD is complicated and needs comprehensive treatment. Lifestyle, food and medical therapies should be combined for best outcomes. Healthcare practitioners and PCOD patients must collaborate to create tailored lifestyle, diet and supplement recommendations. Improve these remedies for the PCOD community with further study.

Keywords: Polycystic Ovarian Disorder (PCOD); Lifestyle; Nutrition; Health Behavior; PCOS

Article Type

Research Article

Introduction

PCOD (Polycystic Ovary Disorder), also known as polycystic ovary syndrome, is a prevalent endocrine condition that affects a significant proportion of women throughout the years in which they are capable of bearing children [1]. This disorder is defined by a complicated interplay of hormonal imbalances, irregular menstrual periods and the presence of several tiny cysts on the ovaries. It is also characterized by the presence of multiple small cysts on the ovaries. In addition to having an effect on fertility, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) often presents itself with a number of disturbing symptoms, some of which include acne, excessive hair growth, weight gain and mood changes [2]. It is becoming more apparent, as the medical profession continues to research the underlying reasons of PCOD, that lifestyle and dietary decisions play crucial roles in both the development and treatment of this disorder. It is common knowledge that aspects of one’s lifestyle, including as one’s food, level of physical activity and ability to deal with stress, may have a substantial impact on the severity and development of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), despite the fact that the specific etiology of PCOS is complicated and not completely known [3]. This awareness has led to a paradigm change in the treatment of PCOD, moving away from a strategy that is only focused on pharmaceuticals and toward a more holistic approach that encompasses lifestyle and nutritional interventions. This transition occurred as a result of an increase in the prevalence of PCOD [4]. This all-encompassing book intends to give a profound and illuminating examination of the complex link that exists between the many lifestyle choices, food habits and PCOD. By diving into the fundamental processes through which lifestyle and nutrition effect PCOD, our goal is to provide people with the information and practical methods they need to take charge of their own health and well-being so they may better manage the condition. In this review, we will investigate several aspects of the topic “Role of Lifestyle and Nutrition in PCOD Management” [5]. This involves investigating the impact that nutrition and lifestyle have on insulin resistance, which is a frequent comorbidity of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), methods for stress reduction also play an important role in the management of PCOS symptoms [6,7]. We will also go into the intricacies of weight management since having a higher-than-normal body mass index is usually connected with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and may make the symptoms of PCOS worse [8]. In addition, we will cover the increasing evidence on certain dietary patterns, such as the influence of low-glycemic diets and the possible advantages of dietary supplements, in the management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) [9]. In this section, we will discuss how important it is for healthcare professionals and nutritionists to have a role in assisting people who have PCOD in making individualized decisions about their food and lifestyle.

Methodology

Our search was limited to publications that were published between January 1, 2000 and May 1, 2023, since we wanted to concentrate on material that was both relevant and current. This timeline was selected to provide access to the most recent and cutting-edge research available on the subject at hand [10]. To retrieve relevant articles and studies, we employed a combination of specific search terms and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) keywords. These search terms and MeSH keywords included:

- “PCOD” OR “Polycystic Ovary Disorder” OR “Polycystic Ovary Syndrome” OR “PCOS”

- “Lifestyle” OR “Diet” OR “Exercise” OR “Physical Activity” OR “Stress Management” OR “Health Behavior”

- “Nutrition” OR “Dietary Patterns” OR “Nutrient Intake” OR “Dietary Interventions” OR “Nutritional Approaches”

Our search was limited to publications that were published between January 1, 1998 and May 1, 2022 so that we could zero in on material that was both relevant and current. This timeline was selected to provide access to the most recent and cutting-edge research available on the subject at hand.

Lifestyle Changes for Improvement of PCOD

Changing one’s lifestyle is the first line of defense in the care of women with PCOS, but it is not a replacement for pharmaceutical intervention [11]. Clinical recommendations for a variety of illnesses emphasize the need of regular physical exercise, keeping an adequate body weight, following good eating patterns and refraining from tobacco use in the prevention and treatment of metabolic disorders. It is up to the individual to prioritize their own physical and mental health; doing so is not a quick cure but does pave the way to a more satisfying existence [11]. PCOS patients have had nutritional counseling as an option for therapy for quite some time. Isocaloric diets, on the other hand, did not substantially enhance biochemical and anthropometric indicators, even when combined with physical exercise and neither did severe calorie restriction [12-14].

Food Intake Management

No significant changes in the levels of the investigated parameters were found when the effects of lifestyle adjustment were studied in relation to the proportion of energy from macronutrients (protein, fat and carbs). The adoption of a low GI, low calorie diet and the subsequent decrease in body weight are two major contributors to these alterations [15,16]. Fasting insulin, total and Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, waist circumference and total testosterone were all lower on low GI (LGI) diets compared to High GI (HGI) diets, while fasting glucose, HDL cholesterol, weight and the free androgen index were not affected [17]. Increases in HDL, Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG) production and body fat loss were also seen when the LGI diet, punitive limits, and/or physical exercise were combined with omega-3 supplementation [18]. Increases in circulation TNF-alpha and peripheral leukocytic Suppressor of Cytokine-3 (SOCS-3) expression were seen after consumption of Saturated Fatty Acids (SFAs), as discovered by Gonzales, et al., [19]. Therefore, it is critical that these patients completely cut out SFA from their diets. Polycystic ovarian syndrome was improved in rats on a diet high in alpha-linolenic acid from flaxseed oil, but similar benefits may be expected from other dietary sources of alpha-linolenic acid [20]. Soluble fiber was shown to have a positive impact on SCFAs. The gut flora benefits metabolically from fermentable fiber, leading to the release of SCFAs [21]. Appetite-regulating hormones including ghrelin and glucagon may be affected by a low GI diet [22]. Ghrelin was decreased and glucagon was raised in PCOS women who ate low glycemic index meals. In PCOS, High Fructose Intake (HFC) was shown to exacerbate endocrine but not metabolic alterations, indicating that HFC may worsen endocrine-related phenotypes. All PCOS patients should be provided expert dietary counseling since a meta-analysis and comprehensive review found that the LGI diet is an effective, acceptable and safe strategy for alleviating IR [23].

The ketogenic diet, which discourages the use of carbs in favor of animal fat, seems to be another low-GI dietary adjustment. Women with PCOS and liver dysfunction may cure fatty liver by following a Ketogenic Diet (KD), which has been shown to normalize the menstrual cycle, lower blood glucose levels and reduce body weight [24]. Using the KD for 12 weeks in women with PCOS, Paoli, et al., [25] revealed even more intriguing findings. A considerable drop in weight (9.43 kg), body mass index (BMI; 3.35) and fat-free body mass (8.29 kg) was found in the anthropometric and body composition tests. Significant improvements in HOMA-IR scores and decreased glucose and insulin levels were also seen. At the same time as HDL levels increased, triglyceride levels, total cholesterol and LDL levels all decreased significantly. Significant decreases were also seen in the LH/FSH ratio, LH total and free testosterone and DHEAS blood levels. A rise in SHBG, estradiol and progesterone was seen. Not drastically, but the Ferriman Gallwey Score went down [26]. Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) was not correlated with hirsutism characteristics. Visceral adipocyte malfunction is not likely to be the cause of hirsutism. As a consequence, a ketogenic diet may provide even greater benefits than an LGI diet in PCOS patients with extreme obesity and/or obesity accompanied by full-blown metabolic syndrome. Nevertheless, a summary conclusion is that the physiological homeostasis may be regulated and quicker recovery from sickness obtained, by adhering to the key principles of a healthy diet.

Physical Activity

Health care providers and PCOS patients alike are coming around to the idea that exercise is an important part of treatment. Exercise amplifies the benefits of insulin sensitivity by enhancing glucose transport and metabolism [27]. Exercise intensity, rather than exercise volume, seems to be the most important factor in improving health outcomes, according to a new meta-analysis. This data lends credence to the utility of exercise and it suggests that high-intensity workouts may have the largest influence on cardiorespiratory fitness, insulin resistance and body composition [28]. There was a moderate and high reduction in insulin resistance as evaluated by the HOMA-IR and body mass index (MD-0.57; 95% CI, 0.98 to 0.16 and p = 0.01; MD-1.90, 95% CI, 3.37 to 0.42 and p = 0.01) [29]. In order to increase insulin sensitivity and decrease androgen levels, other authors in a comprehensive study concluded that PCOS patients should engage in rigorous aerobic activity and strength training. You should get at least 120 minutes of aerobic exercise every week [30].

Sleep

PCOS is related with much more commonly reported states of anxiety, despair and sleep disturbances [31], making it a risk factor for a wide range of mental health problems. Anxiety and sadness are common in women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and research suggests that sleep disturbances have a role in both the genesis and development of these symptoms [32]. Reduced sleep duration is associated with an elevated danger of Insulin Resistance (IR), obesity and T2D [33-35]. The processes that underlie IR in response to sleep deprivation remain poorly understood, although they likely include centrally controlled autonomic pathways, endocrine responses (such as alterations in the important hunger hormones ghrelin and leptin) and inflammatory state. Mice who had their Sleep Disrupted (SF) had increased inflammation in their white adipose tissue (WAT) and Insulin Resistance (IR) as a consequence of “gut leakage” syndrome [36] and LPS-mediated inflammation. Therefore, there is a potential for treatments that target the gut microbiome as a result of SF-induced metabolic abnormalities. Melatonin, produced mostly by the pineal gland, plays a role in regulating the body’s 24-hour clock. Recent studies have shown that individuals with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) had lower melatonin levels in their follicular fluid [37]. Ovarian melatonin receptors and intrafollicular fluid regulate sex steroid release during follicular development. Protecting ovarian follicles from damage during follicular development [38], melatonin is a powerful antioxidant and an efficient free-radical scavenger. Based on what we know today, sleep disturbances are likely one of the first indicators of the decline in protective functions and the amplification of insulin resistance pathways that characterize PCOS [39].

Nutrient Supplements and Complementary Therapies in PCOS

Vitamin Supplements

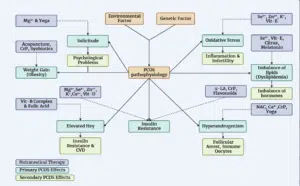

Vitamin D: It’s a crucial nutrient that primarily comes from sunlight exposure and is also found in some foods like oily fish and fortified dairy. Vitamin D plays a vital role in calcium metabolism and maintaining bone health. Some studies suggest that vitamin D supplementation can have positive effects on insulin sensitivity and hormonal balance in women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), particularly when taken daily by those with a deficiency. However, its impact on lipid profiles, inflammation and hyperandrogenism is less certain [40]. Inositol (Vitamin B-8): Inositol, specifically Myo-Inositol (MI) and D-chiro-Inositol (DI), is important for regulating glucose uptake and insulin signaling in the ovaries. Women with PCOS often have imbalances in MI and DI, which can affect glucose metabolism and reproductive health. MI supplementation has been shown to reduce fasting insulin levels and improve insulin resistance. It can also increase Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG) levels, but this effect is more pronounced when MI is administered for at least 24 weeks. Inositol supplementation has been associated with improved ovulation rates, menstrual cycle regulation and hormonal balance in women with PCOS (Fig. 1).

Nutrient Supplements and Complementary Therapies in PCOS

Vitamin Supplements

Vitamin D: It’s a crucial nutrient that primarily comes from sunlight exposure and is also found in some foods like oily fish and fortified dairy. Vitamin D plays a vital role in calcium metabolism and maintaining bone health. Some studies suggest that vitamin D supplementation can have positive effects on insulin sensitivity and hormonal balance in women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), particularly when taken daily by those with a deficiency. However, its impact on lipid profiles, inflammation and hyperandrogenism is less certain [40]. Inositol (Vitamin B-8): Inositol, specifically Myo-Inositol (MI) and D-chiro-Inositol (DI), is important for regulating glucose uptake and insulin signaling in the ovaries. Women with PCOS often have imbalances in MI and DI, which can affect glucose metabolism and reproductive health. MI supplementation has been shown to reduce fasting insulin levels and improve insulin resistance. It can also increase Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG) levels, but this effect is more pronounced when MI is administered for at least 24 weeks. Inositol supplementation has been associated with improved ovulation rates, menstrual cycle regulation and hormonal balance in women with PCOS (Fig. 1).

B-Group Vitamins (B-1, B-6, B-12): B-group vitamins are necessary for processing homocysteine in the blood and preventing its harmful effects. Women with PCOS, especially those taking metformin for insulin resistance, may experience deficiencies in these vitamins. Supplementation with B-group vitamins can help reduce homocysteine levels and potentially improve cardiometabolic and reproductive health. However, their specific impact on insulin resistance remains uncertain based on limited research [42].

Vitamin K: Vitamin K, in the form of K1 (from green vegetables) and K2 (from animal products), is involved in blood coagulation and plays a role in bone and vascular health. Some studies suggest that vitamin K supplementation, specifically vitamin K2, may have beneficial effects on insulin resistance and androgen levels in women with PCOS. However, more research is needed to confirm these findings [43].

Vitamin E: Vitamin E is an antioxidant that can neutralize free radicals. When co-supplemented with other nutrients like coenzyme Q10 or omega-3 fatty acids, it has shown promise in improving insulin resistance and reducing androgen levels in women with PCOS. However, studies focusing solely on vitamin E supplementation in PCOS are limited.

Vitamin A: Vitamin A, also known as retinol, may have a role in metabolic function and androgen production in PCOS. However, there is currently no direct research on vitamin A supplementation in women with PCOS, so its specific effects in this population are unclear [44].

Figure 1: Nutritional supplements and alternative therapies for polycystic ovary syndrome may affect both direct and indirect health outcomes and risk factors. Solid arrows represent escalating effects, whereas dashed arrows represent alleviating ones.

Vitamin-Like Nutrients

Bioflavonoids are plant-derived polyphenolic compounds with antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiestrogenic, anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative properties. Isoflavones, a subgroup of bioflavonoids, have shown interest due to their reported cardioprotective and neuroplasticity-promoting effects. Quercetin, found in apples, berries, grapes and onions, is believed to have metabolic and anti-inflammatory effects. Some studies suggest that quercetin and isoflavones like genistein may improve aspects of PCOS, such as lipid profiles and insulin resistance. However, the evidence is mixed and further research is needed to confirm their efficacy [45].

Carnitine, specifically L-carnitine, plays a role in multiple metabolic processes, including glucose and fatty acid metabolism. Women with PCOS often have lower levels of L-carnitine, which may impact oocyte quality and contribute to insulin and androgen-related issues. L-carnitine supplementation has shown promise in improving insulin sensitivity, BMI and LDL levels in women with PCOS. However, more research is needed to explore its potential benefits further.

Alpha-lipoic acid is an antioxidant and essential cofactor in the citric acid cycle. It has been suggested to regulate body weight by reducing food intake and increasing energy expenditure [46]. Some studies indicate that α-LA supplementation can improve insulin resistance, reduce LDL and triglyceride levels and potentially regulate lipid metabolism. In a study combining α-LA with D-chiro-inositol (DI), improvements were observed in menstrual cycles, ovarian cysts, progesterone levels, BMI and insulin resistance, but further research is required to fully understand its effects in PCOS [46].

Mineral Supplements

CrP contains essential trivalent chromium and has been shown to improve Insulin Resistance (IR), glycemic control, hirsutism and acne in women with PCOS in several Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews. However, there are mixed results from different studies and further research is needed for conclusive evidence of its efficacy.

Women with PCOS often have abnormalities in calcium concentrations, potentially due to deviations in vitamin D and parathyroid hormone. Supplementation with calcium and vitamin D together has shown improvements in various aspects of PCOS, including lipid profiles, menstrual regularity, insulin resistance, hirsutism and testosterone levels [47].

Magnesium is involved in insulin metabolism and neurological functions. Some evidence suggests that magnesium supplementation may help reduce IR in women with PCOS, but more research is needed, especially regarding its effects on depressive symptoms [48].

Selenium is an essential trace element with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functions. Studies have shown that selenium supplementation can reduce IR, inflammation and oxidative stress in women with PCOS. However, results regarding other PCOS features like BMI and hormonal parameters are inconsistent [46,47].

Zinc plays a critical role in insulin synthesis and function. Zinc supplementation has been associated with improvements in HOMA-IR, lipid profiles, inflammation and oxidative stress in women with PCOS. Some trials also noted reductions in free Testosterone (fT), FSH and DHEAS. However, many of these trials used combinations of nutrients, making it challenging to attribute all observed benefits solely to zinc supplementation [48].

Conclusion

In conclusion, polycystic ovarian syndrome, often known as PCOS, is a complicated endocrine illness that affects a considerable percentage of women who are of reproductive age. It is widely recognized that variables related to lifestyle and food play key roles in both the development of PCOS as well as the treatment of this illness. This is despite the fact that the specific causes of PCOS are not completely known. This change in paradigm has resulted in a more holistic approach to treating PCOD, which takes into consideration lifestyle and dietary therapies in addition to medication choices. In this review, we focused on the numerous facets of the role that diet and lifestyle play in the treatment of PCOD. We have spoken about the significance of making adjustments to one’s lifestyle, such as being more active on a regular basis, keeping a healthy body weight, establishing healthy eating habits and learning to effectively manage stress. These changes to one’s way of life are essential to enhancing insulin sensitivity and one’s general well-being when one has Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Our conversation has also centred on the importance of dietary modifications. We have discussed the possible advantages of diets with a low Glycemic Index (GI), ketogenic diets and diets that are abundant in certain nutrients such as inositol, folate, B-group vitamins, vitamin D and others. These dietary strategies may have a beneficial influence on insulin resistance, hormonal equilibrium and other symptoms associated with PCOS. In addition, we have investigated the possibility that taking nutritional supplements, such as chromium picolinate, selenium, magnesium and zinc, might help improve the treatment of PCOS in a variety of different ways.

In addition, issues with sleeping and how they can be connected to PCOS have been examined. A healthy amount of sleep is very necessary for good metabolic function and treating difficulties that are associated with sleep might potentially lead to improved PCOD control. PCOD is a complex disorder that needs an all-encompassing treatment strategy in order to be effectively managed. Individuals who have PCOD may greatly have their quality of life improved by making adjustments to their way of life, such as their diet and lifestyle, in addition to receiving the necessary medical treatment. In order to properly treat this illness, it is vital for persons who have PCOD and healthcare providers to collaborate in order to make individualized choices about lifestyle, nutrition and supplements. It will be necessary to conduct more research in order to better perfect and adapt these therapies to meet the needs of the PCOD community as a whole.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Fauser BC, Tarlatzis BC, Rebar RW, Legro RS, Balen AH, Lobo R, et al. Consensus on women’s health aspects of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertility and Sterility. 2012;97(1):28-38.

- Zuo M, Liao G, Zhang W, Xu D, Lu J, Tang M, et al. Effects of exogenous adiponectin supplementation in early pregnant PCOS mice on the metabolic syndrome of adult female offspring. J Ovarian Res. 2021;14(1):1-2.

- Szczuko M, Zapałowska-Chwyć M, Maciejewska D, Drozd A, Starczewski A, Stachowska E. Significant improvement selected mediators of inflammation in phenotypes of women with PCOS after reduction and low GI diet. Mediators of Inflammation. 2017;2017.

- Ma L, Cao Y, Ma Y, Zhai J. Association between hyperandrogenism and adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients with different polycystic ovary syndrome phenotypes undergoing in-vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021:1-8.

- Martini AE, Healy MW. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: impact on adult and fetal health. Clin Obs Gynecol. 2021;64:26-32.

- Hong G, Wu H, Ma ST, Su Z. Catechins from oolong tea improve uterine defects by inhibiting stat-3 signaling in polycystic ovary syndrome mice. Chin Med. 2020;15:125.

- Szczuko M, Skowronek M, Zapałowska-Chwyć M, Starczewski A. Quantitative assessment of nutrition in patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2016;67:419-26.

- Makki K, Froguel P, Wolowczuk I. Adipose tissue in obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance: cells, cytokines and chemokines. ISRN Inflamm. 2013;2013:139239.

- Dniak-Nikolajew A. Zespół policystycznych jajników jako przyczyna niepłodności kobiecej [polycystic ovary syndrome as a cause of female infertility]. Położna Nauka I Prakt. 2012;17:14-7.

- Mahedi MR, Rawat A, Rabbi F, Babu KS, Tasayco ES, Areche FO, et al. Understanding the global transmission and demographic distribution of Nipah Virus (NiV). Res J Pharm Technol. 2023;16(8):3588-94.

- Moran LJ, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Tomlinson L, Galletly C, Norman RJ. Dietary composition in restoring reproductive and metabolic physiology in overweight women with 12 polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:812-9.

- Tymchuk CN, Tessler SB, Barnard RJ. Changes in sex hormone-binding globulin, insulin and serum lipids in postmenopausal women on a low-fat, high-fiber diet combined with exercise. Nutr Cancer. 2000;38:158-62.

- Gann PH, Chatterton RT, Gapstur SM, Liu K, Garside D, Giovanazzi S, et al. The effects of a low-fat/high-fiber diet on sex hormone levels and menstrual cycling in premenopausal women: a 12-month randomized trial (the diet and hormone study). Cancer. 2003;98:1870-9.

- Moran LJ, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Tomlinson L, Galletly C, Norman RJ. Dietary composition in restoring reproductive and metabolic physiology in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:812-9.

- Szczuko M, Zapałowska-Chwyć M, Drozd A, Maciejewska D, Starczewski A, Wysokiński P, et al. Changes in the IGF-1 and TNF-α synthesis pathways before and after three-month reduction diet with low glicemic index in women with PCOS. Ginekol Pol. 2018;89:295-303.

- Kazemi M, Hadi A, Pierson RA, Lujan ME., Zello GA, Chilibeck PD. Effects of dietary glycemic index and glycemic load on cardiometabolic and reproductive profiles in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Nutr. 2021;12:161-78.

- Szczuko M, Skowronek M, Zapałowska-Chwyć M, Starczewski A. Quantitative assessment of nutrition in patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2016;67:419-26.

- González F, Considine RV, Abdelhadi OA, Acton AJ. Saturated fat ingestion promotes lipopolysaccharide-mediated inflammation and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;104:934-46.

- Wang T, Sha L, Li Y, Zhu L, Wang Z, Li K, et al. Dietary α-Linolenic acid-rich flaxseed oil exerts beneficial effects on polycystic ovary syndrome through sex steroid hormones microbiota inflammation axis in rats. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:284.

- Barber TM, Kabisch S, Pfeiffer AFH, Weickert MO. The health benefits of dietary fibre. Nutrients. 2020;12:3209.

- Szczuko M, Zapalowska-Chwyć M, Drozd R. A low glycemic index decreases inflammation by increasing the concentration of uric acid and the activity of Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx3) in patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) molecules. 2019;24:1508.

- Hoover SE, Gower BA, Cedillo YE, Chandler-Laney PC, Deemer SE, Goss AM. Changes in ghrelin and glucagon following a low glycemic load diet in women with PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021.

- Akintayo CO, Johnson AD, Badejogbin OC, Olaniyi KS, Oniyide AA, Ajadi IO, et al. High fructose-enriched diet synergistically exacerbates endocrine but not metabolic changes in letrozole-induced polycystic ovarian syndrome in wistar rats. Heliyon. 2021;7:e05890.

- Shang Y, Zhou H, Hu M, Feng H. Effect of diet on insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105.

- Porchia LM, Hernandez-Garcia SC, Gonzalez-Mejia ME, López-Bayghen E. Diets with lower carbohydrate concentrations improve insulin sensitivity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obs Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;248:110-7.

- Shishehgar F, Mirmiran P, Rahmati M, Tohidi M, Ramezani TF. Does a restricted energy low glycemic index diet have a different effect on overweight women with or without polycystic ovary syndrome? BMC Endocr Disord. 2019;19:93.

- Paoli A, Mancin L, Giacona MC, Bianco A, Caprio M. Effects of a ketogenic diet in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Transl Med. 2020;18:104.

- Fonseka S, Subhani B, Wijeyaratne CN, Gawarammana IB, Kalupahana NS, Ratnatunga N, et al. Association between visceral adiposity index, hirsutism and cardiometabolic risk factors in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Ceylon Med J. 2019;64:111-7.

- Marson EC, Delevatti RS, Prado AKG, Netto N, Kruel LFM. Effects of aerobic, resistance and combined exercise training on insulin resistance markers in overweight or obese children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2016;93:211-8.

- Patten RK, Boyle RA, Moholdt T, Kiel I, Hopkins WG, Harrison CL, et al. Exercise interventions in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2020;11:606.

- Santos IK, Nunes FA, Queiros VS, Cobucci RN, Dantas PB, Soares GM, et al. Effect of high-intensity interval training on metabolic parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0245023.

- Shele G, Genkil J, Speelman D. A systematic review of the effects of exercise on hormones in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2020;5:35.

- Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Role of sleep and sleep loss in hormonal release and metabolism. Endocr Dev. 2010;17:11-21.

- Donga E, Romijn JA. Sleep characteristics and insulin sensitivity in humans. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;124:107-14.

- Reutrakul S, Van Cauter E. Sleep influences on obesity, insulin resistance and risk of type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2018;84:56-66.

- Poroyko VA, Carreras A, Khalyfa A, Khalyfa AA, Leone V, Peris E, et al. Chronic sleep disruption alters gut microbiota, induces systemic and adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35405.

- Mojaverrostami S, Asghari N, Khamisabadi M, Heidari KH. The role of melatonin in polycystic ovary syndrome: a review. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2019;17:865-82.

- Guo S, Tal R, Jiang H, Yuan T, Liu Y. Vitamin D supplementation ameliorates metabolic dysfunction in patients with PCOS: a systematic review of RCTs and insight into the underlying mechanism. Int J Endocrinol. 2020;2020:1.

- Unfer V, Facchinetti F, Orru B, Giordani B, Nestler J. Myo-inositol effects in women with PCOS: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endocrine Connections. 2017;6(8):647-58.

- Asbaghi O, Ghanavati M, Ashtary-Larky D, Bagheri R, Rezaei KM, Nazarian B, et al. Effects of folic acid supplementation on oxidative stress markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Antioxidants. 2021;10(6):871.

- Kilicdag EB, Bagis T, Tarim E, Aslan E, Erkanli S, Simsek E, et al. Administration of B-group vitamins reduces circulating homocysteine in polycystic ovarian syndrome patients treated with metformin: a randomized trial. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(6):1521-8.

- Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, Ferron M, Ahn JD, Confavreux C, et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell. 2007;130(3):456-69.

- Cicek N, Eryilmaz OG, Sarikaya E, Gulerman C, Genc Y. Vitamin E effect on controlled ovarian stimulation of unexplained infertile women. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(4):325-8.

- Tan BK, Chen J, Lehnert H, Kennedy R, Randeva HS. Raised serum, adipocyte and adipose tissue retinol-binding protein 4 in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome: effects of gonadal and adrenal steroids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2764-72.

- Hosseini A, Razavi BM, Banach M, Hosseinzadeh H. Quercetin and metabolic syndrome: a review. Phytother Res. 2021;35(10):5352-64.

- Masharani U, Gjerde C, Evans JL, Youngren JF, Goldfine ID. Effects of controlled-release alpha lipoic acid in lean, nondiabetic patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(2):359-64.

- Fenkci SM, Fenkci V, Oztekin O, Rota S, Karagenc N. Serum total L-carnitine levels in non-obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(7):1602-6.

- Alesi S, Ee C, Moran LJ, Rao V, Mousa A. Nutritional supplements and complementary therapies in polycystic ovary syndrome. Adv Nutr. 2022;13(4):1243-66.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License.