From Discomfort to Delight: Diet’s Impact on IBS-D

Syed Mahmood Shahidul Islam1*, Md Shanzid Hasan2, Sadia Afrin3, Calvin R Wei4, Mehrab Binte Mushfique5, Abu Saleh6, Mezbah Uddin7, Nikolaos Syrmos8, Md Rezwan Ahmed Mahedi3,9

1Divisional Health and Safety Officer (South Asia and Central Asia); SMEC International Pty Ltd., Bangladesh

2Department of Pharmacy, University of Asia Pacific, Bangladesh

3Department of Pharmacy, Comilla University, Bangladesh

4Department of Research and Development, Shing Huei Group, Taipei, Taiwan

5Holy Family Red Crescent Medical College, Bangladesh

6Department of Public Health Nutrition, Primeasia University, Bangladesh

7Zhengzhou University, China

8Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thesaaloniki, Macedonia, Greece

9Research Secretary, Bangladeshi Pharmacists’ Forum (Comilla University), Bangladesh

*Correspondence author: Syed Mahmood Shahidul Islam, Divisional Health and Safety Officer (South Asia and Central Asia); SMEC International Pty Ltd., Bangladesh; Email: mahmoodshahidul@gmail.com

Citation: Islam SMS, et al. From Discomfort to Delight: Diet’s Impact on IBS-D. Jour Clin Med Res. 2023;4(3):1-10.

Copyright© 2023 by Islam SMS, et al. All rights reserved. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

| Received 05 Sep, 2023 | Accepted 25 Sep, 2023 | Published 02 Oct, 2023 |

Abstract

Introduction: IBS-D is a common gastrointestinal illness that causes lower abdominal discomfort, bloating, changed bowel patterns and poor quality of life. Despite no physical or biochemical problems, IBS-D is debilitating.

Objectives: This review examined the effects of low-FODMAP, gluten-free, lactose-free and fructose-free diets on IBS-D symptoms. We also examined how these diets affected gut microbiota composition and their mechanisms of action.

Methods: A comprehensive literature review was conducted, utilizing databases such as PubMed and Google Scholar. MeSH terms and keywords related to IBS-D, dietary management, gut microbiota and specific dietary approaches were employed in the search. The inclusion criteria were studies published between January 1, 2008 and September 1, 2023, to ensure the inclusion of recent and relevant research. Selected studies were critically reviewed for their findings on the effects of dietary interventions on IBS-D symptoms and the gut microbiota.

Results: Several dietary strategies, including the gluten-free diet, fructose-free diet, lactose-free diet and low-FODMAP diet have demonstrated promise in alleviating IBS-D symptoms, particularly diarrhea, bloating and abdominal pain. These diets have shown varying degrees of success, with some individuals experiencing significant symptom improvement. Furthermore, alterations in gut microbiota composition have been observed in response to dietary modifications, although the exact mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated.

Conclusion: This review suggests dietary changes may improve IBS-D symptoms and the gut microbiome. However, the intricacy of dietary impacts on IBS-D requires further investigation to determine their effectiveness and gut microbiota impact. Individualized diets may help IBS-D patients relieve symptoms and improve gut health. Dietary suggestions for IBS-D treatment need more study.

Keywords: IBS-D; Diet; FODMAP; Microbiota; GIT

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome is characterized by abdominal pain during or after bowel motions [1,2]. It is more frequent in women under 50, although anyone may have it [2,3]. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) causes bowel habit changes, gas, stomach pain, incomplete evacuation and urgency [2,3]. However, no physical or metabolic disorders cause the problem. The effect of IBS on patients’ QoL may cause work and daily life issues [2,4,5]. A diagnosis is based on symptoms after radiologic or endoscopic diagnostics rule out other GI illnesses [2,3]. There is continuous dispute regarding the relative involvement of numerous variables in irritable bowel syndrome [2,3]. These include gastrointestinal motility changes, visceral hypersensitivity, SIBO, environmental factors-particularly diet-and intestinal flora changes.

Recent studies examined the hypomorphic Sucrase-Isomaltase (SI) gene variant as a possible cause of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea (IBS-D) [6,7]. SI insufficiency is a condition in which the brush border of the small intestine is unable to generate adequate sucrase-isomaltase. The fermentation of undigested disaccharides produced from starch and sucrose in the colon is the root cause of these symptoms [6,7]. This fermentation causes stomach discomfort, bloating and osmotic diarrhoea. This deficiency, according to Kim, et al., should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with IBS-like symptoms [7]. Furthermore, ISD might be primary (genetic) or secondary (duodenal villus atrophy or inflammation) [7].

IBS Roma IV Criteria (Bristol Stool Scale) | |

Constipation Prominent IBS (IBS-C) | < 25% loose stools and > 25% hard stools. |

Diarrhea Predominant IBS (IBS-D) | < 25% hard stools and > 25% loose stools. Approximately 40% of patients seem to fall under this group. |

Mixed Bowel Habits IBS (IBS-M) | > 25% loose stools and > 25% hard stools |

Unclassified IBS (IBS-U) | < 25% loose stools and < 25% hard stools |

Table 1: IBS Classification based on Roma IV criteria (Bristol Stool Scale) [8-10].

This review examined the effects of low-FODMAP, gluten-free, lactose-free and fructose-free diets on IBS-D symptoms. We also examined how these diets affected gut microbiota composition and their mechanisms of action.

Method

In order to better understand the connection between nutrition and irritable bowel syndrome with Diarrhea (IBS-D), we performed a comprehensive literature review. By using MeSH terms like “IBS classification,” “IBS-D diet management,” “Gut microbiota IBS-D,” “Low-FODMAP diet IBS-D,” and “Dietary triggers IBS-D,” we searched credible resources like PubMed. In order to include only the most up-to-date and relevant studies, this extensive search was restricted to those published between January 1, 2008 and September 1, 2023. After reading the selected research, our team assembled to discuss our findings and form outcomes concerning diet and IBS-D. Our goal was to learn more about how diet affects IBS-D symptoms, what foods may be triggers and how certain diets, like the low-FODMAP diet, might help people with IBS-D feel better.

Psychological Mechanism for IBS-D (Serotonin Based)

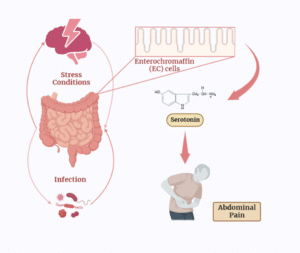

The neurotransmitter serotonin, well recognized for its part in regulating mood, also has a major influence on gastrointestinal health and disorders, including Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhoea (IBS-D). The gastrointestinal system’s serotonin synthesis and release affect many aspects of gut function, such as motility, secretion and feeling. Enterochromaffin (EC) cells, which are entero-endocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract, create 90% of the serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, or 5HT) in the human body [11]. Enterochromaffin cells in the gastrointestinal system secrete serotonin, which stimulates muscle contractions in the intestines. It may stimulate afferent nerve terminals and is a crucial mediator in gastric secretion and motility. The amount of EC cells may be different in patients with IBS; however, the data is assorted. Certain studies [12,13] have connected an increase in EC cells in the colonic and rectal mucosa to Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome (PI IBS). Researchers Cremon, et al., found an increased concentration of 5HT-positive cells in the colon biopsies of people with IBS compared to controls [14]. In IBS patients, serotonin release was 10 times higher than in healthy volunteers, which was significantly correlated with mast cell counts and the severity of stomach pain. These results suggest that increased serotonin levels may contribute to the beginning of pain in irritable bowel syndrome by activating the mucosal immune system [15]. However, other researchers have shown no change in the number of EC cells in the small intestine and the colon between IBS patients and controls [17]. The biological activity of the 5HT Transporter (SERT) is lower in people with IBS, according to recent research [18]. This suggests that those who suffer from IBS may have altered 5HT mucosal signaling (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: A schematic representation of serotonin that can induce the IBS-D type symptoms like rapid bowel movement or cramps, lower abdomen pain, etc.

Pathogenic Mechanism for IBS-D

A bacterial infection may cause symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), especially if the illness harms or permanently changes the gut. Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome (PI-IBS) occurs, for instance, after a bacterial gastrointestinal illness like gastroenteritis. Persistent symptoms similar to those of IBS-D may result from the infection changing gut motility, increasing intestinal permeability and affecting the gut-brain axis [19]. Visceral pain is caused by toxins that depolarize nociceptive neurons and break down the integrity of the epithelium [20]. This makes the mucosa more permeable. Certain pathogenic bacteria create N-formylated peptides [21]. These peptides have a role in the perception of visceral pain by activating formyl peptide receptors and triggering the release of inflammatory mediators, both of which contribute to the experience of pain. Nociceptor neurons are directly activated by N-formylated peptides and the pore-forming toxin hemolysin produced by Staphylococcus aureus [22]. A growing body of research suggests that these microbial metabolites contribute to dysbiosis, which in turn affects low-grade inflammation-mediated nociception in IBS [23].

Changes in the Gut Microbiota

Host-microbial interactions in the gut may play a role in the development of irritable bowel syndrome. About 1014 cells make up the human microbiota, with the vast majority residing in the colon [24]. The observation that formerly healthy people may develop IBS after contracting gastroenteritis provides credence to the PI IBS theory [25]. It is unclear how the gut microbiome contributes to irritable bowel syndrome. Effects on intestinal functions such as motility, secretion, barrier function and the brain-gut axis are possible [44]. The stool microbiota of patients with irritable bowel syndrome is distinct from that of healthy individuals [26,27]. Jeffery, et al., found that in people with IBS, a longer colon transit time and feeling sad were both linked to a rise in taxa related to Firmicutes and a drop in taxa related to Bacteroidetes [28]. The precise association between Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is still up for dispute [29,30]. Whether or not SIBO testing is essential for all people with IBS is still up for debate. Additional evidence linking gut flora to the pathogenesis of IBS comes from the successful treatment of IBS patients with rifaximin or probiotics [31-33].

Nutritional Strategies for IBS with Diarrhea

Approximately eighty-four percent (84%) of people with IBS attribute their symptoms to the foods they consume particularly fermentable carbohydrates and lipids [34-36]. Patients who try to identify the foods they think are triggering their symptoms and exclude them entirely from their diet risk falling nutritionally short and becoming physically exhausted [37,38]. Eating some meals may result in fermentation, altering intraluminal pH and the microbiota, in addition to osmotic, chemical, mechanical and neuroendocrine effects [39]. Because of this, patients often benefit from receiving nutritional instruction on how to make healthy food choices alongside conventional medical care [40]. Researchers have looked for an appropriate diet to manage IBS; however, there is limited evidence for IBS-D.

Conventional Dietary Guidelines

Patients with IBS should initially try making behavioral and dietary changes. Dietary changes are based on recommendations from the British Dietetic Association and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [41,42]. These recommendations stress the need for eating at regular intervals, consuming adequate amounts of fiber and fluids, limiting one’s consumption of fatty and spicy foods and restricting one’s use of alcohol and caffeine (Table 2) [43].

1 | Eat regularly and in reasonable amounts |

2 | Avoid skipping meals |

3 | Drink about 2 liters of liquids every day, preferably water |

4 | Reduce caffeine consumption to under three cups daily |

5 | Cut down on sodas and alcoholic beverages |

6 | Reduce your fiber intake since it may be related to your symptoms showing up. They need to cut down on insoluble fiber (cereals with bran or cereals made with bran, whole wheat flour and its derivatives). Instead, you should consume soluble fibers like oat or Psyllium (Ispaghula) |

7 | Reduce “resistant starch” found in processed and packaged foods by eating less |

8 | Limit fresh fruit to three 80-gram portions per day |

9 | Sugar-free drinks, gum and other products contain sorbitol, which diabetics should avoid |

Table 2: Patients with IBS should initially try making behavioral and dietary changes.

Figures and Data

Adopting Low-FODMAP Diet

A low-FODMAP (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols) diet has been designed to reduce the consumption of these short-chain carbohydrates since they are fermented and not absorbed in the colon. Foods high in Fermentable Oligosaccharides and Monosaccharides (FODMAPs) include dairy products, wheat, as well as vegetables, legumes, artificial sweeteners, fruits and processed meals. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) sufferers and those with IBS-D in particular, may find relief by following this diet, which has been an area of extensive research.

In the first trial of its sort in the United States, researchers Eswaran, et al., tracked participants for four weeks and randomly assigned them to either the low-FODMAP diet or the modified NICE (mNICE) diet [44]. Using questionnaires, the researchers were able to measure the symptoms reported by people in both diet groups, allowing for a direct comparison. Patients with IBS-D were randomly assigned to follow either the mNICE diet or the low-FODMAP diet based on the Rome III criteria. Despite the fact that following a low-FODMAP diet drastically lowers FODMAP consumption, the first piece of advice was to eat smaller, more frequent meals free of possible trigger items and to cut down on or completely cut out alcohol and caffeine. The low-FODMAP diet was much more effective than the mNICE diet in alleviating symptoms, which only occurred in 40-50% of patients. These people had significant reductions in their stomach discomfort and diarrhea. There were additional assessments of mental health indicators such as anxiety, sleep quality, quality of life, work output, activity impairment, depression and exhaustion [45]. We observed that the low-FODMAP diet significantly improved overall performance. People with IBS-D who have one or two copies of a gene variant that codes for sucrase-isomaltase are less likely to benefit from the low-FODMAP diet [46].

The health benefits related to a low-FODMAP diet were compared to those of following regular dietary guidelines in a randomized, controlled experiment by Zahedi, et al., that lasted for 6 weeks. When compared to the other diet, the low-FODMAP diet significantly improved symptom relief and bowel regularity [47,48]. From the beginning through the completion of the experiment, there was no statistically significant difference in quality of life between the two diets. One hundred and one people with IBS-D were randomly assigned to either a low-FODMAP diet with no more than 0.5 g of FODMAP per serving or a diet based on traditional dietary guidelines and both were asked to adhere to their assigned diets for four weeks. Both diets had the same total calorie count. The patient started receiving further nutritional counseling in the form of a modified low-FODMAP diet after weeks 4 through 16 of this first treatment. Ninety-nine patients advanced to phase II (lasting 14 weeks) because they maintained a 50% compliance rate or greater throughout phase I (lasting 4 weeks). Patients who followed a low-FODMAP diet, either strictly or with some adjustments, had fewer symptoms and required less medication, according to the study. In addition, adherence was high and ultimately, 64.1% of patients were able to restore FODMAPs to their diets without any adverse effects. A possible cause is that they were very driven to raise their standard of living.

Gluten-Free Diet (GFD)

People who have been treated for IBS may still find relief from their symptoms by adhering to a gluten-free diet, despite the fact that the prevalence of celiac disease is considered to be higher in IBS-D than in other types of IBS [49]. Celiac illness and gluten sensitivity share certain symptoms with irritable bowel syndrome, including diarrhea [50]. Recent studies have indicated that individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) have a worsening of symptoms after ingesting gluten or wheat, suggesting that avoiding these foods may help alleviate IBS symptoms [51]. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has been linked to both gluten sensitivity and the use of certain foods. However, Guidelines 2020 recommend that those with IBS-D undergo serological testing for celiac disease prior to receiving dietary recommendations [52]. Gluten and other wheat components may or may not have a role in symptom development, although this is not yet known. Wheat Sensitivity (WS) has replaced the formerly popular HLA-DQ2/8 genotype as the preferred nomenclature for this condition. According to research by Barmeyer, et al., 34% (14 HLA-DQ2/8 positive and 21 HLA-DQ2/8 negative) of 35 non-celiac people with wheat sensitivity said they felt better after going on a wheat-free GFD [53].

Lactose-Free Diet (LFD)

The lactase enzyme is required for the breakdown of the disaccharide lactose into the simpler monosaccharide’s galactose and glucose. Enzyme production occurs near the small intestine’s apical brush edge. Age is associated with a decline in lactase activity [54]. Without proper digestion in the small intestine, lactose ends up in the colon. Lactose-Intolerant (LI) patients have problems digesting lactose because the microbiota in their intestines convert it into Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) and other gases [55]. Irritable BOWEL SYNDROME (IBS) sufferers often avoid lactose-containing foods, such as dairy products, since eating them may dramatically exacerbate their symptoms [56]. People with IBS-D who believe their own reports of milk intolerance consistently predict LI typically choose lactose-free choices because of this misconception [57]. People with Irritable Bowel Syndrome Type D seem to be more likely to be lactose intolerant than the general population, despite the fact that lactose intolerance is not necessarily related to malabsorption [58-60]. IBS-D patients with lactose intolerance are different from IBS-D patients with simple lactose malabsorption or healthy controls because they have a rise in rectal sensitivity after taking lactose, a rise in serum TNF alpha and an increase in mast cells in the intestinal mucosa [61].

Fructose-Free Diet (FFD)

It is common practice to recommend a fructose-free diet for those who have fructose malabsorption or who have positive results on a fructose breath test [62,63]. Twenty-six of eighty participants in a breath analysis study of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) were fructose intolerant and all of these fructose-intolerant participants also had IBS symptoms such as diarrhea or loose stools. Only 14 of 26 fructose-intolerant persons reported improvement in symptoms (such as diarrhea, stomach pain, bloating, indigestion, fullness and burping) after restricting fructose consumption for nearly a year [64].

Plant-Based and Vegetarian Diet

The staples of a vegetarian’s diet are plant-based and include things like legumes, grains, crops, roots, fruit, oilseeds, vegetables, mushrooms and nuts. There are several health advantages to a vegetarian diet [65]. A vegan diet is distinct from a vegetarian one in that it excludes all forms of animal-based food, although it shares many of the latter’s principles, such as a focus on eating a wide variety of fruits and vegetables and a reduction in both salt and saturated fat [66]. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus thrive in the gut microbiome of vegetarians, but pathogenic Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium perfringens are absent. The ratio of these elements is what determines how much SCFA production increases [67]. There are several distinctions between the conventional microbiome profile and the vegan one [68]. For instance, the vegan microbiota has fewer pathobionts and more defensive species. According to research by Matijai, et al., vegetarians and vegans had a higher ratio of the Bacteroides-Prevotella group and a lower ratio of the Clostridium cluster XIV alpha [69]. The population of people with IBS-D has to be investigated further.

Limitation

The absence of high-quality data supporting the dietary treatments addressed is a major weakness of this study. Many studies may have methodological flaws or small sample numbers, which might impair the reliability of the results; nonetheless, there is some encouraging evidence on the benefits of low-FODMAP, gluten-free, lactose-free and fructose-free diets on IBS-D symptoms. Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea (IBS-D) is a complex disorder with a wide range of potential causes and precipitating factors. Distinct forms of IBS-D may have distinct dietary intervention responses; however, this review does not always distinguish between them. The results may not be generalizable to all patient populations because of the absence of stratification.

Managing symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-D) may be challenging and many research on dietary treatments have very short durations, which may not reflect the long-term benefits or durability of these diets. More extensive research is required to evaluate the long-term impact on both symptom persistence and safety. Although the research implies that diets tailored to individual IBS-D patients may be helpful, it does not give clear suggestions on how to do so. The results aren’t very useful since there aren’t any specific dietary suggestions for each individual. It is unclear how exactly these diets affect IBS-D symptoms and the make-up of the gut flora. The review does not give thorough insights into the particular routes involved, while acknowledging the intricacy of these interactions. This evaluation covers articles published up through September 2023. Since new information on IBS-D emerges all the time, the results of studies conducted after the time period in question may be different [70-76].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the relationship between the foods we eat and the symptoms of IBS is complicated. There is also little scientific evidence to support the use of any particular dietary approach for IBS; rather, clinical practice offers the bulk of the advice. The possibility that dietary changes might aid with gastrointestinal problems is fascinating. But at the moment, there is no evidence supporting a diet that may reliably promote eubiosys and reduce IBS-D symptoms among patients with a high rate of compliance. This dietary regimen alleviates symptoms (particularly gas, stomach discomfort and diarrhea but it also decreases the relative abundance of numerous butyrate makers and in turn, health-associated bacteria (i.e., Bifidobacteria). Avoiding gluten has several benefits, one of which is a reduction in irritable bowel syndrome (Type D) symptoms. Therefore, it is quite challenging to choose a diet that may ameliorate IBS-D symptoms and restore eubiosis; further research is required to achieve this objective. Few clinical studies examined the correlation between diet, microbiota and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) symptoms and the overwhelming majority of those studies did not account for the varied forms of IBS. Finding the right diet to improve symptoms and microbiota composition may depend on knowing the form of IBS a person has. Given the current lack of information, further studies are required to assess whether or not these individuals might benefit from changing their diet to modify the makeup of their gut microbiota and in turn, improve their symptoms.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterol., 2016;150(6):1393-407.

- Lacy BE, Moreau JC. Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: Diagnosis, etiology and new treatment considerations. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2016;28(7):393-404.

- Alammar N, Stein E. Irritable bowel syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(1):137-52.

- Cangemi DJ, Lacy BE. Management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: a review of nonpharmacological and pharmacological interventions. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:175628481987895.

- Zahedi MJ, Behrouz V, Azimi M. Low fermentable oligo-di-mono-saccharides and polyols dietversusgeneral dietary advice in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial: Diet in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33(6):1192-9.

- Zheng T, Eswaran S, Photenhauer AL, Merchant JL, Chey WD, D’Amato M. Reduced efficacy of low FODMAPs diet in patients with IBS-D carrying Sucrase-Isomaltase (SI) hypomorphic variants. Gut. 2020;69(2):397-8.

- Kim SB, Calmet FH, Garrido J, Garcia-Buitrago MT, Moshiree B. Sucrase-isomaltase deficiency as a potential masquerader in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(2):534-40.

- Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L, Sadik R, Abrahamsson H, Tack J, Simrén M. Colonic transit time and IBS symptoms: what’s the link? Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(5):754-60.

- Keszthelyi D, Troost FJ, Masclee AA. Irritable bowel syndrome: methods, mechanisms and pathophysiology. Methods to assess visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303(2):G141-54.

- Ritchie J. Pain from distension of the pelvic colon by inflating a balloon in the irritable colon syndrome. Gut. 1973;14(2):125-32.

- Furness J. Constituent neurons of the enteric nervous system. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. 2006.

- Lee KJ, Kim YB, Kim JH, Kwon HC, Kim DK, Cho SW. The alteration of enterochromaffin cell, mast cell and lamina propria T lymphocyte numbers in irritable bowel syndrome and its relationship with psychological factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(11):1689-94.

- Kim HS, Lim JH, Park H, Lee S. Increased immunoendocrine cells in intestinal mucosa of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome patients 3 years after acute Shigella infection-an observation in a small case control study. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51(1):45-51.

- Cremon C, Carini G, Wang B, Vasina V, Cogliandro RF, De Giorgio R, et al. Intestinal serotonin release, sensory neuron activation and abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(7):1290-8.

- Park JH, Rhee PL, Kim G, Lee JH, Kim Y-h, Kim JJ, et al. Enteroendocrine cell counts correlate with visceral hypersensitivity in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(7):539-46.

- Faure C, Patey N, Gauthier C, Brooks EM, Mawe GM. Serotonin signaling is altered in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea but not in functional dyspepsia in pediatric age patients. Gastroenterol. 2010;139(1):249-58.

- Coates MD, Mahoney CR, Linden DR, Sampson JE, Chen J, Blaszyk H, et al. Molecular defects in mucosal serotonin content and decreased serotonin reuptake transporter in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol. 2004;126(7):1657-64.

- Foley S, Garsed K, Singh G, Duroudier NP, Swan C, Hall IP, et al. Impaired uptake of serotonin by platelets from patients with irritable bowel syndrome correlates with duodenal immune activation. Gastroenterol. 2011;140(5):1434-43.

- Peraro MD, Van Der Goot FG. Pore-forming toxins: Ancient, but never really out of fashion. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:77-92.

- Van Thiel IA, Botschuijver S, de Jonge WJ, Seppen J. Painful interactions: Microbial compounds and visceral pain. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(1):165534.

- Chiu IM, Heesters BA, Ghasemlou N, Von Hehn CA, Zhao F, Tran J, et al. Bacteria activate sensory neurons that modulate pain and inflammation. Nature. 2013;501(7465):52-7.

- Guo R, Chen LH, Xing C, Liu T. Pain regulation by gut microbiota: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Br J Anaesthesia. 2019;123(5):637-54.

- Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Kynurenine pathway metabolism and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Neuropharmacol. 2017;112:399-412.

- Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(3):859-904.

- Spiller R, Garsed K. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol. 2009;136(6):1979-88.

- Simrén M, Barbara G, Flint HJ, Spiegel BM, Spiller RC, Vanner S, et al. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut. 2013;62(1):159-76.

- Jeffery IB, O’Toole PW, Öhman L, Claesson MJ, Deane J, Quigley EM. An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut. 2012;61(7):997-1006.

- Kassinen A, Krogius-Kurikka L, Mäkivuokko H, Rinttilä T, Paulin L, Corander J, et al. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterol. 2007;133(1):24-33.

- Grover M, Kanazawa M, Palsson OS, Chitkara DK, Gangarosa LM, Drossman DA, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome: association with colon motility, bowel symptoms and psychological distress. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(9):998-1008.

- Posserud I, Stotzer PO, Björnsson ES, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2007;56(6):802-8.

- Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, Zakko S, Ringel Y, Yu J, et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(1):22-32.

- Saadi M, McCallum RW. Rifaximin in irritable bowel syndrome: rationale, evidence and clinical use. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2013;4(2):71-5.

- Moayyedi P, Ford AC, Talley NJ, Cremonini F, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Brandt LJ, et al. The efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Gut. 2010;59(3):325-32.

- Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, Svedlund J, Abrahamsson H, Bengtsson U, et al. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2001;63(2):108-15.

- Monsbakken KW, Vandvik PO, Farup PG. Perceived food intolerance in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome – etiology, prevalence and consequences. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(5):667-72.

- Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, Bengtsson U, Simrén M. Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):634-41.

- Halpert A, Dalton CB, Palsson O, Morris C, Hu Y, Bangdiwala S, et al. What patients know about Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and what they would like to know. National survey on patient educational needs in IBS and development and validation of the Patient Educational needs Questionnaire (PEQ). Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(9):1972-82.

- Dapoigny M, Stockbrügger RW, Azpiroz F, Collins S, Coremans G, Müller-Lissner S, et al. Role of alimentation in irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2003;67(4):225-33.

- Spencer M, Chey WD, Eswaran S. Dietary renaissance in IBS: Has food replaced medications as a primary treatment strategy? Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12(4):424-40.

- Cartabellotta A, Patti AL, Berti F. Linee guida per la gestione della sindrome dell’intestino irritabile negli adulti. Evidence. 2016;8:e1000130.

- Mahedi MR, Rawat A, Rabbi F, Babu KS, Tasayco ES, Areche FO, et al. Understanding the global transmission and demographic distribution of Nipah Virus (NiV). Res J Pharm Technol. 2023;16(8):3588-94.

- McKenzie YA, Bowyer RK, Leach H, Gulia P, Horobin J, O’Sullivan NA, et al. British Dietetic Association systematic review and evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29(5):549-75.

- Rej A, Aziz I, Tornblom H, Sanders DS, Simrén M. The role of diet in irritable bowel syndrome: implications for dietary advice. J Intern Med. 2019;286(5):490-502.

- Cuomo R, Andreozzi P, Zito FP, Passananti V, De Carlo G, Sarnelli G. Irritable bowel syndrome and food interaction. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8837-45.

- Eswaran SL, Chey WD, Han-Markey T, Ball S, Jackson K. A randomized controlled trial comparing the low FODMAP diet vs. Modified NICE guidelines in US adults with IBS-D. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1824-32.

- Eswaran S, Chey WD, Jackson K, Pillai S, Chey SW, Han-Markey T. A diet low in fermentable oligo-, Di- and monosaccharides and polyols improve quality of life and reduces activity impairment in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(12):1890-9.

- Goyal O, Batta S, Nohria S, Kishore H, Goyal P, Sehgal R, et al. Low fermentable oligosaccharide, disaccharide, monosaccharide and polyol diet in patients with diarrhea‐predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective, randomized trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(8):2107-15.

- Usai-Satta P, Bassotti G, Bellini M, Oppia F, Lai M, Cabras F. Irritable bowel syndrome and gluten-related disorders. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1117.

- Makharia A, Catassi C, Makharia G. The overlap between irritable bowel syndrome and non-celiac gluten sensitivity: A clinical dilemma. Nutrients. 2015;7(12):10417-26.

- Chey WD. Food: The main course to wellness and illness in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:366-71.

- Volta U, Pinto-Sanchez MI, Boschetti E, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Verdu EF. Dietary triggers in irritable bowel syndrome: Is there a role for gluten? J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22(4):547-57.

- De Giorgio R, Volta U, Gibson PR. Sensitivity to wheat, gluten and FODMAPs in IBS: facts or fiction? Gut. 2016;65(1):169-78.

- Savaiano DA, Levitt MD. Milk intolerance and microbe-containing dairy foods. J Dairy Sci. 1987;70:397-406.

- Lomer MC, Parkes GC, Sanderson JD. lactose intolerance in clinical practice-myths and realities. Alimentary Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(2):93-103.

- Fassio F, Facioni M, Guagnini F. Lactose maldigestion, malabsorption and intolerance: A comprehensive review with a focus on current management and future perspectives. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):1599.

- Xiong L, Wang Y, Gong X, Chen M. Prevalence of lactose intolerance in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: data from a tertiary center in southern China. J Health Popul Nutr. 2017;36(1).

- Yang J, Fox M, Cong Y, Chu H, Zheng X, Long Y, et al. Lactose intolerance in irritable bowel syndrome patients with diarrhoea: the roles of anxiety, activation of the innate mucosal immune system and visceral sensitivity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(3):302-11.

- Varjú P, Gede N, Szakács Z, Hegyi P, Cazacu IM, Pécsi D, et al. Lactose intolerance but not lactose maldigestion is more frequent in patients with irritable bowel syndrome than in healthy controls: A meta‐analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(5).

- Yang J, Deng Y, Chu H, Cong Y, Zhao J, Pohl D, et al. Prevalence and presentation of lactose intolerance and effects on dairy product intake in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(3):262-8.

- Deng Y, Misselwitz B, Dai N, Fox M. Lactose intolerance in adults: Biological mechanism and dietary management. Nutrients. 2015;7(9):8020-35.

- Lisker R, Solomons NW, Briceño RP, Mata MR. Lactase and placebo in the management of the irritable bowel syndrome: A double-blind, cross-Over study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:756-62.

- Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Fructose malabsorption and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: Guidelines for effective dietary management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(10):1631-9.

- Choi YK, Kraft N, Zimmerman B, Jackson M, Rao SSC. Fructose intolerance in IBS and utility of fructose-restricted diet. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(3):233-8.

- Feng Z. Role of dietary nutrients in the modulation of gut Microbiota: A narrative review. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):381.

- Pilis W, Stec K, Zych M, Pilis A. Health benefits and risk associated with adopting a vegetarian diet. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2014;659:14.

- Chandra-Hioe MV, Lee C, Arcot J. What is the cobalamin status among vegetarians and vegans in Australia? Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2019;70(7):875-86.

- Singh RK, Chang H-W, Yan D, Lee KM, Ucmak D, Wong K, et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1).

- Glick-Bauer M, Yeh MC. The health advantage of a vegan diet: Exploring the gut microbiota connection. Nutrients. 2014;6(11):4822-38.

- Matijašić BB, Obermajer T, Lipoglavšek L, Grabnar I, Avguštin G, Rogelj I. Association of dietary type with fecal microbiota in vegetarians and omnivores in Slovenia. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53(4):1051-64.

- Suzuki T, Yoshida S, Hara H. Physiological concentrations of short-chain fatty acids immediately suppress colonic epithelial permeability. Br J Nutr. 2008;100(2):297-305.

- Lloyd DA, Powell-Tuck J. Artificial nutrition: Principles and practice of enteral feeding. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17:107-18.

- Romick-Rosendale LE, Haslam DB, Lane A, Denson L, Lake K, Wilkey A, et al. Antibiotic exposure and reduced short chain fatty acid production after hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(12):2418-24.

- Cabré E. Irritable bowel syndrome: can nutrient manipulation help? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13(5):581-7.

- Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Salonen A, Nikkilä J, Immonen O, Kekkonen R, Lahti L, et al. Intestinal microbiota in healthy adults: Temporal analysis reveals individual and common core and relation to intestinal symptoms. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e23035.

- Altomare A, Di Rosa C, Imperia E, Emerenziani S, Cicala M, Guarino MPL. Diarrhea predominant-Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-D): Effects of different nutritional patterns on intestinal dysbiosis and symptoms. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1506.

- Ahmed Mahedi MR. Finding the causes of the concretion between asthma and urticaria: A narrative review. J Clin Immun Microbiol. 2023;1-7.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License.