Fatima Salek1*, Kadri Hassani Mohamed El Fatmi2, Faouzi Azaroual3, Fatima Zaoui4

1Specialist in Dentofacial Orthopedics, University Mohamed V Faculty of Dental Medicine of Rabat – Mohamed V University, Allal El Fassi Avenue, Mohamed Jazouli Street, Madinat Al Irfane 6212, Rabat-Instituts, Morocco

2Former Professor and Former Head of Department ORL and Cevico-Facial Surgery, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery; Hospital of August 20, Casablanca, Morocco

3Professor in Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Morocco

4Professor and Head of the Department of Dentofacial Orthopedics of Faculty of Dental Medicine of Rabat, Morocco

Published Date: 12-02-2024

Copyright© 2024 by Salek F, et al. All rights reserved. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: Class III malocclusions and anterior crossbites are disturbing for patients because they are very apparent and often cause aesthetic and functional damage.

Description: The clinical case describes a 19-year-old patient in good general health attended the dento-facial orthopedics service at the Rabat Hospital Center for Dental Consultation and Treatment presenting an anterior crossbite. The clinical examination and the cephalometric analysis showed that the patient had a Class III malocclusion of maxillary and mandibular origin with hyperdivergent facial type. An orthodontic-surgical treatment was well indicated for correction of the skeletal discrepancy in three phases: presurgical orthodontic preparation, orthognathic surgery and orthodontic finishing.

Results: In reviewing the patient’s final records, the major goals set at the beginning of treatment were successfully achieved; the facial profile and proportion were significantly improved with solid functional occlusion

Conclusion: In class III malocclusion when facial aesthetics is altered, the surgical-orthodontic treatment is the most indicated for patients who do not present facial growth.

Keywords: Class III Malocclusion; Orthodontic Preparation; Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomy; Maxillary Advancement; Maxillary Impaction

Introduction

Etiologically Class III malocclusions are multifactorial which includes genetic and environmental factors. The prevalence of class III malocclusion varies by ethnicity [1-6]. Among the hard-tissue structures involved in Class III malocclusions, there are some variations such as mandibular prognathism, maxillary retrusion or a combination of both [7]. Maxillary deficiency is more frequent, accounting for 60-63% of the causes of this type of malocclusion [8]. Maxillary skeletal deficiency can also be associated with deficiency of the middle third of the face, confirmed by the contour of the zygomatic bone, orbital ridge and sub pupillary area. Intraoral examination reveals increased axial inclination of the maxillary incisors and decreased axial inclination of the mandibular incisors in an attempt to mask the real maxilla mandibular discrepancy [7]. A complete evaluation of the dentition, the patient lips, smile and the entire face represents the basis of a correct diagnosis. Therefore, the establishment of the treatment plan is based on the efficacy and thoughtful application by the clinician and easy acceptance by the patient [9]. This case report presents orthosurgical management of an adult patient with skeletal Class III malocclusion.

Case Report

A 19-year-old man was referred to the Department of Orthodontics of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Rabat, Mohammed V University – Rabat with the chief complaint of forwardly placed lower front teeth and impaired speech that has led to low level of self-confidence. The medical history of the patient did not show any contraindications to combined orthodontic-surgical treatment.

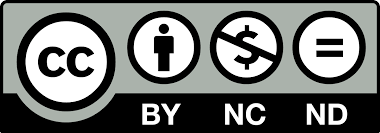

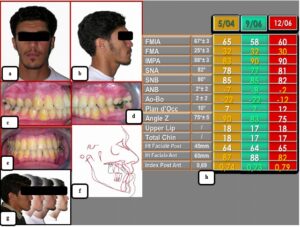

Extraoral Examination (Fig. 1)

Facial clinical examination revealed an asymmetrical long oval face with a deviation of the chin on the left, an increase of the lower facial height and a little zygomatic bone expression. The profile was straight. As in most Class III cases, the middle region of the face was deficient. The patient had a slightly increased lower face height; the lower lip was slightly prominent. Temporomandibular joint examination did not reveal any discrepancy between centric relation and/centric occlusion and patient did not complain of pain or clicking in the joint.

Intraoral Examination (Fig. 1)

Intraoral examination showed absence of 16 and 26, slight deviation of the mandibular midline to the left, class III molar and canine relationships (10 mm) on both sides, as well as an anterior crossbite with a negative overjet of 5 mm.

Radiographic Examination

The panoramic radiographic examination confirms the absence of 16 and 25 (Fig. 1). The lateral cephalometric radiograph (figure 1 and 5) revealed Class III skeletal malocclusion (ANB = -7°, AoBo=-22mm) with retrognathic maxilla, (SNA= 78°), prognathic mandible (SNB = 85°), increased lower face height (SN/GoGn = 40° and FMA = 32°), proclined maxillary incisors (I. NA= 30° and I-NA= 7 mm) and retroclined mandibular incisors (i. NB = 20° and i-NB= 4 mm)

Figure 1: a-b: pre-treatment extra-oral photographs; c-d-e: pre-treatment intra-oral photographs; f: Initial panoramic radiograph; g: Initial profile radiograph.

Treatment Objectives

- Alignment of both the arches with proper angulations of all the teeth

- Correct the dental compensations,

- Promote maxillary impaction and advancement and mandibular retrusion for correction of the dental relationship and skeletal Class III

- Correction of negative overjet

- Functional Class I molar relationship

- Establishing a Class I skeletal relationship

- Achieving acceptable static and functional occlusion

- Improving the soft tissue profile

Treatment Progress

- Initially, the 28, 38 and 48 were extracted followed by placement of fixed appliances. Levelling and alignment phases were performed using a preadjusted edgewise (022” x 0.28”) in order to eliminate dentoalveolar compensations. These phases were performed using the following arch sequence: .014” NiTi, .016”NiTi, 018”NiTi, 018”× .025” NiTi. 018” × .025” SS, 019” × .025” SS and 021” × .025” SS

- Subsequently, retraction of the maxillary incisors was performed after the alignment and closure of incisor diastemes, maintaining the anchorage with Class II intermaxillary elastics

- The intercuspation was confirmed by occluding the plaster models. After obtaining satisfactory intercuspation of the plaster models, soldered hooks were placed on a 021” × .025” stainless steel archwires in all inter-bracket spaces

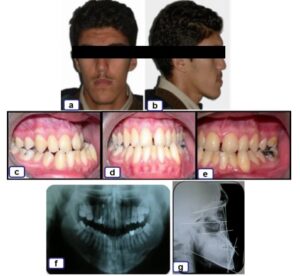

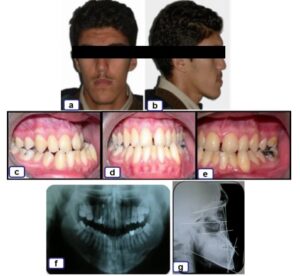

- A control X-ray (Fig. 2) was necessary before surgery; it shows the cephalometric values after orthodontic preparation

Figure 2: a-b: pre-surgical extra-oral photographs; c-d-e: pre-surgical intra-oral photographs; f: pre-surgical panoramic radiograph; g: pre-surgical profile radiograph.

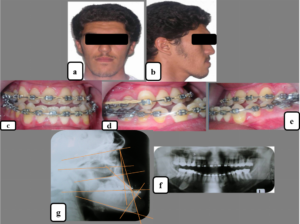

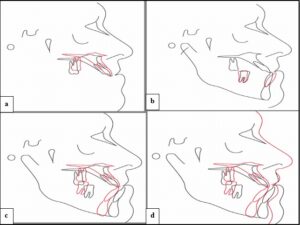

From a surgical point-of view, the cephalometric set-up (Fig. 3) after orthodontic decompensation prescribed the following targets:

- For the maxilla, posterior impaction of 2 mm and at the same time advancement of 3 mm

- For the mandible, a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (7 mm)

Figure 3: Pre-surgical set-up. a: Maxillary advancement /impaction; b: Orthodontic part; c: Surgical mandibular setback; d: Soft tissue changes.

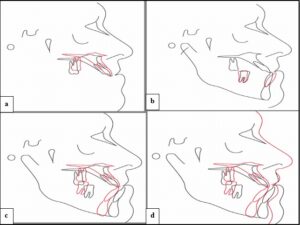

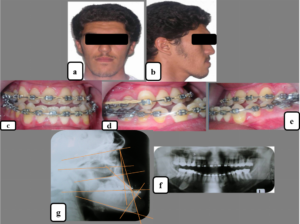

After surgery, the patient returned for orthodontic finishing for obtaining Class II molar (on the left), class I molar on the right relationship, class I canine relationship and normal overjet and overbite (Fig. 4). Patient was kept on class III elastics to prevent any relapse post-surgically for 6 weeks.

Figure 4: a-b: post-surgical extra-oral photographs; c-d-e: post-surgical orthodontic finishing (face, profile and occlusion).

After the active treatment phase, a stainless steel 3×3 lingual canine-to-canine retainer was placed in the maxillary and mandibular arches.

Results

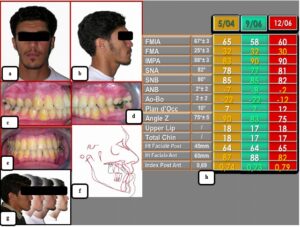

Posttreatment records (Fig. 5) showed that all treatment objectives were achieved with good esthetic and occlusal results (Fig. 5): facial symmetry was achieved, dental midlines were coincident with the facial midline and ideal overjet and overbite were obtained.

Cephalometric measurements (Fig. 5) showed that successful dental decompensation and surgical correction of the skeletal Class III jaw discrepancy were achieved: SNB decreased from 85° to 82°, the ANB angle and the AoBo increased from -8°to -2° and from -22 to -12 mm, respectively. The mandibular incisors inclination relative to the mandibular plane (IMPA) was maintened (IMPA=90°). The maxilla moved forward with a slight posterior impaction, the mandible underwent a closing rotation (FMA decreased from 32° to 30°) and the nose tip moved upward as a result of the maxillary advancement.

Figure 5: a-b: end of treatment extra-oral photographs; c-d-e: end of treatment intra-oral photographs; f: superimpositions of tracings during orthodontic treatment, before surgery and after the end of treatment; g: Comparison of facial views; h: cephalometric values before, during and after orthodontic-surgical treatment.

For the functional objectives, there were no signs or symptoms of temporo-mandibular disorder. Overall, he was satisfied with the improvement in his facial appearance and his normalized occlusal function.

Discussion

Clinically, Class III malocclusion is in two forms: (a) “pseudo or functional Class III,” due to an early interference with the muscular reflex of mandibular closure and (b) the “true skeletal Class III” [10]. The etiology of Class III malocclusion is multifactorial, with genetic, ethnic, environmental and habitual components [4]. It was believed until 1970 that only the mandible is responsible for class III malocclusion; however, almost 30 to 40% of patients exhibit some degree of maxillary deficiency [5,11].

Compared with Class I control groups, Class III subjects usually showed a shorter anterior and posterior cranial base, a smaller saddle angle and a shorter maxillary length, but a normal maxillary position and a longer mandibular length. In addition, these patients usually exhibit an increase in lower face height and a larger gonial angle, more protrusive maxillary incisors, upright mandibular incisors and a retrusive upper lip.

The diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of class III malocclusion have always been a challenge for clinicians. A normal occlusion and improved facial esthetics of skeletal class III malocclusion can be achieved by growth modification, orthodontic camouflage or orthognathic surgery. The age of the patient, severity of the malocclusion, patient’s chief complaint, clinical examinations and cephalometric analysis will delineate the treatment of choice [12].

However, the decision as to which treatment should be chosen is not always an easy task especially in borderline cases. For this reason, the treatment outcome of camouflage and surgical orthodontic treatment has been studied. Rabie, et al., evaluated borderline class III patients who had undergone camouflage orthodontic treatment or orthognathic surgery and suggested that Holdaway angle can be a reliable guide in determining the treatment modality of these patients [13]. They further suggested that patients with a Holdaway angle greater than 12° can be successfully treated by orthodontics alone while patients with Holdaway angles less than 12° would require surgical treatment. In a similar study, Benyahia, et al., reported the limit value of this angle was 7.2 ° [14]. Therefore, a patient whose angle H is less than this value must be treated by an orthodontic surgery approach.

One of the main objectives of the pre-surgical orthodontic phase is to correct incisor inclinations by retroclining the proclined maxillary incisors and proclinating the retroclined mandibular incisors to a more normal axial inclination and to allow a maximum surgical correction. This increases the severity of the class III dental malocclusion and often results in a less esthetic facial profile before the surgery (Fig. 2) [15,16].

In the surgical treatment of Class III patients, a number of studies on stability after maxillary advancement and mandibular setback have reported that the maxillary advancement is relatively stable [16-19]. As well as an isolated mandibular setback is often unstable. Indeed, during surgery, the patient is in a supine position and the condylar relaxation is common. Therefore, the condyles reposition themselves after the intermaxillary fixation and the mandible moves forward, mimicking a surgical relapse. For this reason, almost all Class III patients now have maxillary advancement, either alone or (more frequently) combined with mandibular setback.

The combined surgical-orthodontic treatment of this case led to a significant facial, dental and functional improvement. The dental relationship achieved was good. Facially, vertical balance and harmony were obtained and this is perhaps the most important goal achieved, because it was the patient’s chief concern (Fig. 5).

Conclusion

In class III malocclusion when facial aesthetics is altered, the surgical-orthodontic treatment is the most indicated for patients who do not present facial growth. A correct diagnosis and planning as well as an appropriate execution of the treatment plan are determinant factors for having success and long-term stability. In the case presented in this report, surgical orthodontic treatment combined with bilateral sagittal split osteotomy and maxillary advancement and impaction was effective for proving adequate masticatory function and pleasant facial esthetics.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Dr Kadri Hassani Mohamed El Fatmi for his contribution in this work by performing bimaxillary surgery for the patient.

References

- Proffit WR, Fields HW, Sarver DM, Ackerman JL. Contemporary Orthodontics. St. Louis. Mo: Mosby. 2000;276-7.

- Sharma R, Arora V, Sindhu D. Management of class III malocclusion with Facemask therepy and comprehensive orthodontic treatment: a case report. Int J Enhanced Research in Med Dental Care. 2017;4(7).

- Baccetti T, Tollaro I. A retrospective comparison of functional appliance treatment of class III malocclusions in the deciduous and mixed dentitions. Eur J Orthod. 1998;20:309-17.

- Campbell PM. The dilemma of Class III treatment. Angle Orthod. 1983;53:175-91.

- Kapust AJ, Sinclair PM, Turley PK. Cephalometric effects of face mask/expansion therapy in class III children: a comparison of three age groups. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113:204-12.

- Atalay Z, Tortop T. Dentofacial effects of a modified tandem traction bow appliance. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:655-61.

- Janson G, Santana E, De Castro RC, De Freitas MR. Orthodontic-surgical treatment of class III malocclusion with extraction of an impacted canine and multi-segmented maxillary surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:840-9.

- Turley P. Orthopedic correction of class III malocclusion with palatal expansion and custom protection headgear. J Clin Orthod. 1988;22:314-25.

- Parrello D, Bolamperti L, Caprioglio A. Interdisciplinary treatment of Ccass III malocclusion: a case report. Progress in Orthodontics. 2011;12(2):169-79.

- Moyers RE. Handbook of orthodontics. Year Book Medical Publishers. 1988.

- Arman A, Toygar TU, Abuhijleh E. Profile changes associated with different orthopedic treatment approaches in class III malocclusions. The Angle Orthodontist. 2004;74(6):733-40.

- Eslami S, Faber J, Fateh A, Sheikholaemmeh F, Grassia V, Jamilian A. Treatment decision in adult patients with class III malocclusion: surgery versus orthodontics. Prog Orthod. 2018; 19(1):28.

- Rabie AB, Wong RW, Min GU. Treatment in borderline class III malocclusion: orthodontic camouflage (extraction) versus orthognathic surgery. Open Dent J. 2008;2:38-48.

- Benyahya H, Azaroual MF, Garcia C, Hamou E, Abouqal R, Zaoui F. Treatment of skeletal class III malocclusions: Orthognathic surgery or orthodontic camouflage? How to decide Int Orthodont. 2011;9:196-209.

- Azamian Z, Shirban F. Treatment options for class III malocclusion in growing patients with emphasis on maxillary protraction. Scientifica (Cairo). 2016;2016:8105163.

- Mora HR, Guzmán VI, Olivar CM, Miranda HÓ. Surgical-orthodontic treatment for skeletal class III correction. Case report. Revista Mexicana de Ortodoncia. 2016;4:260-70.

- Arpornmaeklong P, Shand JM, Heggie AA. Stability of combined Le Fort I maxillary advancement and mandibular reduction. Australian Orthod J. 2003;19:57-66.

- Abeltins A, Jakobsone G, Urtane I, Bigestans A. The stability of bilateral sagittal ramus osteotomy and vertical ramus osteotomy after bimaxillary correction of class III malocclusion. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39:583-7.

- Chang HH, Lin CH, Ko EW. Surgical-orthodontic correction of skeletal class III anterior open bite with facial asymmetry. Taiwanese J Orthodont. 2023;35(2):2.

Article Type

Case Report

Publication History

Received Date: 22-01-2024

Accepted Date: 04-02-2024

Published Date: 12-02-2024

Copyright© 2024 by Salek F, et al. All rights reserved. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: Salek F, et al. Orthodontic-Surgical Correction of a Skeletal Class III Malocclusion: Case Report. J Dental Health Oral Res. 2024;5(1):1-8.

Figure 1: a-b: pre-treatment extra-oral photographs; c-d-e: pre-treatment intra-oral photographs; f: Initial panoramic radiograph; g: Initial profile radiograph.

Figure 2: a-b: pre-surgical extra-oral photographs; c-d-e: pre-surgical intra-oral photographs; f: pre-surgical panoramic radiograph; g: pre-surgical profile radiograph.

Figure 3: Pre-surgical set-up. a: Maxillary advancement /impaction; b: Orthodontic part; c: Surgical mandibular setback; d: Soft tissue changes.

Figure 4: a-b: post-surgical extra-oral photographs; c-d-e: post-surgical orthodontic finishing (face, profile and occlusion).

Figure 5: a-b: end of treatment extra-oral photographs; c-d-e: end of treatment intra-oral photographs; f: superimpositions of tracings during orthodontic treatment, before surgery and after the end of treatment; g: Comparison of facial views; h: cephalometric values before, during and after orthodontic-surgical treatment.