Torgny Sjödin1*, Rolf Movert2, Mikael Åström3

1PhD, Department of Oral Biology and Pathology, Faculty of Odontology, Malmö University, SE-205 06, Malmö, Sweden

2Chemical Engineer, Reséns väg 16D, SE-373 32 Nättraby, Sweden

3PhL, StatCons, Högerudsgatan 8B, SE-216 18 Malmö, Sweden

*Corresponding Author: Torgny Sjödin, Department of Oral Biology and Pathology, Faculty of Odontology, Malmö University, SE-205 06, Malmö, Sweden; Email: [email protected]

Published Date: 18-02-2022

Copyright© 2022 by Sjödin T, et al. All rights reserved. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this article was to perform a reanalysis of the adverse recordings from Phase III studies of Decapinol Mouthwash (containing 2 mg/mL of the active ingredient delmopinol HCl) on patients with gingivitis with respect to occurrence of aphthous stomatitis.

Materials and Methods: The adverse events recordings from 8 randomized double-blind clinical studies on patients with gingivitis were statistically evaluated with respect to presence of aphthous stomatitis. The patients were treated for 2-6 months with mouthwashes containing delmopinol HCl 0.2%, delmopinol HCl 0.1%, chlorhexidine digluconate 0.2% or placebo. The number of visits in each study was three. Each time the patients visited the dentist for efficacy determinations, also data like adverse events were recorded. The number of patients with aphthous stomatitis at the different visits was calculated. Meta-analysis using the Fisher’s exact test was performed to evaluate how the effect was related to the different treatments.

Results: After 4-6 weeks, the patients rinsing with delmopinol HCl 0.2% was the only group showing a significantly better effect than the placebo group.

After 2-3 months, all groups rinsing with the delmopinol or chlorhexidine solutions showed statistically significantly better efficacy data than the placebo group. There was no statistically significant difference between the different treatments with active ingredient.

After 5-6 months no statistically significant effect over placebo was observed for any of the treatments.

Conclusion: The ability of delmopinol to reduce the incidence of aphthous stomatitis was found to be superior to placebo and at least as good as chlorhexidine. Further clinical studies designed for patients with Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis (RAS) should be performed to determine the effectiveness of delmopinol.

Keywords

Delmopinol; Decapinol; Aphthous Stomatitis; Clinical Study

Introduction

Delmopinol is a tertiary amine surfactant, developed as an anti-plaque agent to reduce plaque and gingivitis as an adjunct to normal mechanical cleaning where this has proved inadequate. In opposite to some other anti-plaque chemicals, including chlorhexidine, which owe their effectiveness to a combination of bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity, delmopinol was developed to have comparably low antimicrobial properties, and by interfering with plaque matrix formation promote a microbial flora compatible with dental health [1-9].

A large number of phase I-II clinical studies has been performed to study the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of a mouthwash formulation of delmopinol hydrochloride [10-16]. These studies ended up with presenting a mouthwash formulation, Decapinol® Mouthwash, containing 2 mg/mL of delmopinol hydrochloride, intended for oral rinse during 1 min and then to be expectorated. Eight double-blind, parallel-group designed phase III studies were thereafter carried out. The studies were conducted by different and independent university based research groups in five different European countries, showing that rinsing with Decapinol Mouthwash 2 mg/mL fulfilled the ADA effectiveness criteria for controlling plaque and gingivitis [17-22].

In a recent paper, the influence of delmopinol on the oral mucosa was studied, and it was shown that delmopinol was rapidly adsorbed and retained in this tissue [23]. It was suggested that the interaction between delmopinol and mucosal surfaces should be of great importance for the pharmacokinetics of delmopinol as well as for some adverse effects (a transient numbing sensation and taste disturbances), but possibly also for a reduction of the frequency in occurrence of aphthous stomatitis, spontaneously reported by patients in the phase III studies. The purpose of this paper was to further analyse the clinical data with respect to this finding.

Methods

Study Design

All phase III studies were randomized, double-blind with a parallel-group design, where five studies involved supervised rinsing and three involved unsupervised rinsing. The length of the studies was 2-6 months.

The patients rinsed twice daily (morning and evening) for 60 seconds with 10 mL Decapinol Mouthwash 2 mg/mL (containing delmopinol HCl 2 mg/ml, subsequently called delmopinol 0.2%) or placebo (the vehicle of Decapinol Mouthwash). In some studies chlorhexidine digluconate 2 mg/mL (Hibitane Dental® 0.2%, subsequently called chlorhexidine 0.2%) or Decapinol Mouthwash 1 mg/mL (subsequently called delmopinol 0.1%) was used as active control. Packaging and labelling of the solutions were carried out following Good Manufacturing Procedures at independent Clinical Service Departments and were dispensed in identical amber glass bottles.

The patients included in the studies had a mild to severe gingivitis, with a frequency of bleeding on probing from about 25% to more than 95%. The range of age was from 18 to 73 years, with about 10% of the patients older than 40 years. Fifty percent of the patients had pockets of 4 mm or deeper and 22% pockets of 5 mm or deeper. The deepest pocket was 10 mm. Patients with more than four pockets deeper than 5 mm were excluded from the studies. Both genders were included in the studies except in studies DEC-89016, DEC-89017 and DEC-90018 where all patients were men. In total about 60% were men and 40% women. The major part of the patients (61%) were non-smokers and 20% were regular smokers. The remaining 20% smoked “sometimes”. In order to ensure a balanced design, patients were allocated to treatment groups according to a computer-generated randomization list. Further details regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in the meta-analysis paper of Addy, et al. [17].

Sub and supragingival professional cleaning was administered to all patients in every study after these baseline assessments had been completed, and they were instructed to continue with habitual oral hygiene measures and to use their usual toothpaste. Any rinsing undertaken in conjunction with tooth brushing was to be performed after mechanical cleaning. Special attention was paid to the blindness. Thus, one investigator measured the efficacy variables and another person was appointed to handle the adverse events questioning, observations and recording. Both investigators were unaware of the determinations made by the other investigator and used separate Case Record Forms (CRF).

Each time the patients visited the institution for efficacy determinations, also other data like adverse events and concomitant medication were recorded. The number of visits in each study was three (baseline, interim, end) except in one of the studies (DEC-91023) with four visits (baseline, 6 weeks, 3 months, 5 months).

Spontaneously reported adverse events as well as adverse events observed at the time of the inspection of the oral cavity by the dentist were recorded at every visit. In addition, the patients were asked if they had been disturbed by any ailments or had other troubles since their last visit.

The protocols of all the studies were approved by local ethics committees and the trials themselves were conducted in accordance with the provisions and principles of the World Medical Assembly Declaration of Helsinki (1964 and later amendments) and Good Clinical Practice (GCP).

Statistics

To evaluate if the effect on aphthous stomatitis was related to treatment with delmopinol, an analysis pooling data from all studies and using the Fisher’s exact test was performed with 2-sided p-values. The data from 2 and 3 months were pooled, but include patients from different studies (no patient was thus reported twice). The same was true for the 5 and 6-months data.

Result

The number of patients and length of treatment in the phase III program are shown in Table 1. The table also shows which studies that were supervised and unsupervised. The percentages of patients completing treatment according to Intention-to-treat at end of study were 98%, 99%, 97% and 87% for placebo, delmopinol 0.1%, delmopinol 0.2% and chlorhexidine 0.2%, respectively.

Study Number | Number of Patients Entering Treatment | Treatment Length | Study Site | |||

Placebo | Delmopinol 0.1% | Delmopinol 0.2% | Chlorhexidine 0.2 % | |||

DEC-89016* | 40 | 40 | 40 | – | 8 weeks | Dep. of Periodontol, Inst. of Postgraduate Dental Education, Jönköping, Sweden |

DEC-89017* | 39 | 44 | 38 | – | 8 weeks | Dep. of Periodontol, University of Umeå, Sweden |

DEC-90014* | 53 | – | 53 | 50 | 6 months | Dep.of Periodontology, University of Bern, Switzerland |

DEC-90018* | 46 | – | 49 | 48 | 6 months | Dep. of Periodontolgy, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden |

DEC-90019 | 157 | 157 | 156 | – | 3 months | Dep. of Periodontol, University of Dublin, Ireland |

DEC-90023* | 51 | – | 50 | 52 | 5 months | School of Dental Medicine, University of Brussels, Belgium |

DEC-91025 | 150 | 150 | 150 | – | 6 months | University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff |

DEC-91027 | 150 | 151 | 150 | – | 3 months | Dep. of Periodontology, Faculty of Medicine, Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium |

Total number | 686 | 542 | 686 | 150 | ||

* The asterisk indicates that the rinsing in the study was supervised. | ||||||

Table 1: Number of patients and length of treatment in the phase III programme.

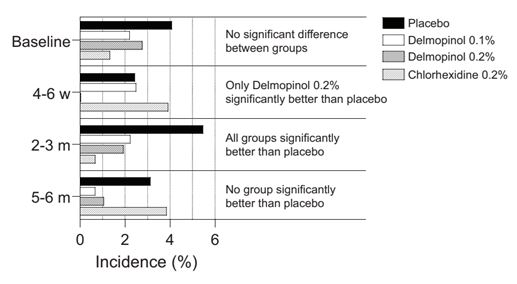

Fig. 1 and 2 give a short presentation of the data in Supplemental Tables 1-7. The Tables show the number of patients in each study and treatment group (ITT-analysis), the number of patients (n) with aphthous stomatitis (#) at the different visits, as well as the p-values of the statistical calculations. The Fisher’s exact test with 2-sided p-values was used for the statistical calculations when testing if the percentage of patients having aphthous stomatitis were equal in the groups.

As can be seen in Fig. 1 (Supplemental Table 1), there was no significant difference at baseline between the treatment groups with respect to the number of aphthous stomatitis, even if the placebo group contained a comparably high number of reports. As expected, the number of patients found to have aphthous stomatitis was low, since aphthous stomatitis was not used as a criterium for inclusion or exclusion in the studies.

After 4-6 weeks (Fig. 1, Supplemental Table 2), the patients rinsing with delmopinol 0.2% was the only group with a significantly better effect than the placebo group. The delmopinol 0.2% group was also significantly more efficient in comparison with delmopinol 0.1% and chlorhexidine 0.2%. Thus, patients rinsing with delmopinol 0.2% showed a significantly lower frequency of aphthous stomatitis than the patients in all other groups.

After rinsing for 2-3 months (Fig. 1, Supplemental Table 3), all groups rinsing with the delmopinol or chlorhexidine solutions showed significantly better efficacy data than the placebo group, and there was no significant difference between the different treatments with active ingredient.

After 5-6 months no significant effect over placebo was observed for any of the different treatments (Fig. 1, Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 1: Percentage of patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline and after for 4-6 weeks, 2-3 months and 5-6 months.

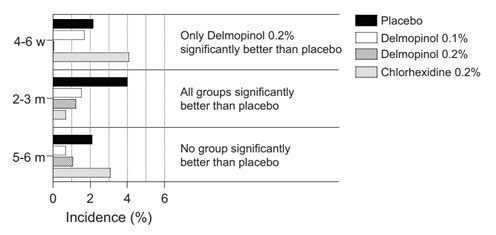

Statistical evaluations were also performed by including only those patients having no observed aphthous stomatitis at the baseline visit. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline were thus excluded from the calculations and the results are presented in Fig. 2. It was found that very similar results were obtained as in the previous set of calculations. Thus, after 4-6 weeks (Supplemental Table 5) as well as after 2-3 months (Supplemental Table 6) and 5-6 months (Supplemental Table 7) the same overall results were obtained for the different test groups as in Fig. 1 (Supplemental Tables 2-4).

Figure 2: Percentage of patients without aphthous stomatitis at baseline and after 4-6 weeks, 2-3 months and 5-6 months.

Discussion

Oral aphthousis is a painful ulceration of mucus membranes and is one of the most common oral mucosal disorders. It is characterized by the formation of oral mucosal lesions that affect primarily the non-keratinised mucosa [24]. The lesions are generally recurrent, but the frequency and intensity of the lesions decrease with age [25,26]. Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis (RAS) is divided into three forms: minor, major and herpetiform, where the minor form is the most common one and is responsible for 70% to 85% of all RAS and with a resolution time of 10 to 14 days [27,28]. The cause of aphthousis is still poorly understood, but viral and bacterial infections, immune or endocrine disturbances, mechanical injuries, genetic factors and nutritional deficiensis have all been implicated as etiological factors of frequent oral ulcerations [27]. At present there is no cure. Only symptomatic therapy is available and treatments aim to decrease pain, reduce healing time and reduce the frequency of recurrence.

The phase III studies presented in this paper were conducted by independent university-based research groups of high academic standing in the field of oral hygiene research (Table 1) and in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice. The studies were part of the preclinical and clinical development program for Decapinol Mouthwash 2 mg/mL, where delmopinol HCl was the active ingredient. The purpose of these clinical studies was to evaluate the efficiency and safety of the product. To our knowledge, these are the only phase III studies that have been performed with Decapinol Mouthwash. A meta-analysis of these clinical trials was published by Addy, et al., where data on effectiveness as well as side-effects are presented [17].

The purpose of these phase III studies was thus to study the safety and effectiveness of a mouthwash containing delmopinol as the active ingredient against plaque and gingivitis. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were therefore chosen to give a balanced patient population with respect to age, gender, degree of gingivitis etc. [17]. For the same reason chlorhexidine 0.2% was included as a positive control in some of the studies, since chlorhexidine is well recognised for its effective anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis properties. The patients as well as the positive control were thus not chosen to fit studies on aphthae, and the data presented in this paper should be regarded as secondary findings obtained from the lists of adverse events recordings.

In all studies special efforts were made to keep the studies double blind. This was important, since a common side-effect of delmopinol is the experience of a surface anaesthetic sensation. The efficacy determinations were therefore separated from the adverse events recordings by using two independent investigators. Adverse events were assessed by an investigator who did not measure the efficacy variables and vice versa. Thus, the studies can be considered double blind. Also, the comparison between delmopinol 0.1% and 0.2% is interesting as there were no problem in this case to keep the blindness.

Based upon the notations in the adverse recording list, most probably the overwhelming part of the patients with aphthous lesions should be defined as minor RAS. This is a condition that will last for about 1-2 weeks [27,28]. Thus, even if some of the patients were noticed to have aphthous stomatitis at baseline, one can assume that this should not affect the readings 4-6 weeks later, which was the time for the first visit time. However, in order to investigate this further, a second set of statistical calculations were performed where patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline were excluded from the calculations. As can be seen, a comparison of the data in the two sets of Tables (Supplemental Tables 2-4 versus Supplemental Tables 5-7) give the same results.

The data clearly shows that a solution of delmopinol significantly reduce the frequency of aphthous stomatitis in comparison with a placebo solution. Furthermore, the short term data (4-6 weeks) suggest that delmopinol 0.2% is more effective than both delmopinol 0.1% as well as chlorhexidine 0.2%. The number of patients included in the 2-3 months data is comparably high in all groups (except the chlorhexidine group), which increases the reliability to conclude that both delmopinol 0.1% and delmopinol 0.2% effectively reduces the number of incidents with aphthous lesions. However, at this time point there was no statistically significant difference between the two delmopinol solutions, even if the data seems to suggest an advantage for delmopinol 0.2%. Surprisingly, none of the solutions with delmopinol or chlorhexidine was statistically significantly better than placebo after 5-6 months, and despite the comparably high incidence of aphthous stomatitis in the chlorhexidine group neither delmopinol 0.1% nor 0.2% appeared to be better than chlorhexidine 0.2%.

As already mentioned, these clinical studies were part of the development of delmopinol 0.2% for prevention of plaque and gingivitis. The positive side-effect shown on aphthous stomatitis was thus obtained on a formulation, handling instructions as well as study lengths that were developed for other indications. Further clinical studies, designed to evaluate the effects of delmopinol 0.2% on patients with RAS, should be performed in order to get information about to what extent treatment with delmopinol 0.2% may decrease pain and ulcer size, promote healing and decrease frequency of recurrence. Furthermore, it is possible that the positive effect of delmopinol on RAS can be further improved, since each therapy requires distinct handling procedures and formulations in order to optimize treatment and minimize side effects [29]. Based upon our experiences with delmopinol 0.2%, the following aspects should then be considered:

First, the original delmopinol 0.2% formulation was used containing in addition to water only the active ingredient delmopinol hydrochloride, a flavouring agent, a sweetening agent and a solvent agent (ethanol 1.5%). No preservatives or other agents were present, since they may interfere with the actions of delmopinol. For stability reasons, the pH of the delmopinol formulation was adjusted to pH 5.7, where delmopinol is in its water soluble cationic form. The mouthwash solution was not buffered, however, thereby allowing the saliva of the rinsing person to immediately increase the pH of the solution close to neutral pH. This means that delmopinol, with a pKa-value of 7.1, to great extent will be transformed from its cationic to its non-ionic form, which is rapidly adsorbed and retained in the oral mucosa for up to 4 hours and successively released out of this tissue into the systemic circulation [23]. The complex adsorption of delmopinol can be explained by the pKa-value for delmopinol, the great difference in water solubility between its cationic and non-ionised forms, the pH of the system as well as the concentration of delmopinol in the administered solution [30,31]. In this context it should be mentioned that in contrast to delmopinol, chlorhexidine does not penetrate into the oral mucosa, since no detectable levels of chlorhexidine was found in blood samples from patients rinsing for 6 weeks with a 0.2% solution of chlorhexidine digluconate [32]. This could explain a difference in the mechanism of action between the two compounds.

Second, the patients rinsed twice daily for 1 minute. Shorter rinse time (30 seconds) has been suggested on the delmopinol products on the market. However, there are no clinical data supporting a shorter rinse time than 1 min. All clinical rinse studies with delmopinol have used a rinse time of 1 min, except for a clinical cross-over study phase II study looking at the inhibition of plaque growth and determination of pharmacokinetic parameters in healthy volunteers rinsing for 15, 30 or 60 seconds. That study showed that the clinical efficacy of delmopinol in terms of prevention of plaque development was improved with increasing rinse time [15]. Based upon the pharmacokinetic results obtained in the same study, it was found that the mucosal penetration of delmopinol in terms of AUC-values was also increased with longer rinse time, which may be an important factor for the efficacy of delmopinol against aphthous stomatitis.

The treatment approach of RAS depends on the frequency, size and number of ulcers and topical agents are usually the first option of treatment [33]. A large number of topical medications are available and regarded as effective for most patients, and chlorhexidine is often mentioned as an example of such agents [27,33-35]. Thus, even if chlorhexidine was included as a positive control in the studies of delmopinol on gingivitis, chlorhexidine should be of value also when comparing the effect between these compounds with respect to aphthous stomatitis. According to this study, the effectiveness of delmopinol for treatment of aphthous stomatitis seems to be at least as good as chlorhexidine, and coupled with its qualitatively and quantitatively greatly reduced potential for tooth staining [17,21], makes this compound potentially an attractive alternative to chlorhexidine.

Conclusion

A mouthwash formulation with delmopinol has shown promising results with respect to aphthous stomatitis in phase III studies on patients with gingivitis. Further clinical studies should be performed on patients suffering of RAS in order to determine the effectiveness of delmopinol to reduce the recurrence of aphthous ulcerations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Pär Matsson, University of Gothenburg, for the statistical calculations.

References

- Simonsson T, Hvid EB, Rundegren J, Edwardsson S. Effect of delmopinol on in vitro dental plaque formation, bacterial acid production and the number of microorganisms in human saliva. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1991;6:305-9.

- Steinberg D, Beeman D, Bowman W. The effect of delmopinol on glucosyltransferase adsorbed on to saliva-coated hydroxyapatite. Arch Oral Biol. 1992;37:33-8.

- Simonsson T, Arnebrant T, Petersson L. The effect of delmopinol on salivary pellicles, the wettability of tooth surfaces in vivo and bacterial cell surfaces in vitro. Biofouling. 1991;3:251-60.

- Rundegren J, Arnebrant T. Effect of delmopinol on the viscosity of extracellular glucans produced by Streptococcus mutans. Caries Res. 1992;26:281-5.

- Rundegren J, Simonsson T, Petersson L, Hansson E. Effect of delmopinol on the cohesion of glucan-containing plaque formed by Streptococcus mutans in a flow cell system. J Dent Res. 1992;71:1792-6.

- Simonsson T, Arnebrant T, Petersson L, Hvid EB. Influence of delmopinol on bacterial zeta-potentials and on the colloidal stability of bacterial suspensions. Acta Odontol Scand. 1991;49:311-6.

- Rundegren J, Sjödin T, Petersson L, Hansson E, Jonsson I. Delmopinol interactions with cell walls of gram-negative and gram-positive oral bacteria. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1995;10:102-9.

- Vassilakos N, Arnebrant T, Rundegren J. In vitro interactions of delmopinol hydrochloride with salivary films adsorbed at solid/liquid interfaces. Caries Res. 1993;27(3):176-82.

- Neilands J, Troedsson U, Sjödin T, Davies JR. The effect of delmopinol and fluoride on acid adaptation and acid production in dental plaque biofilms. Arch Oral Biol. 2014;59(3):318-23.

- Collaert B, Attström R, de Bruyn H, Movert R. The effect of delmopinol rinsing on dental plaque formation and gingivitis healing. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:274-80.

- Collaert B, Edwardsson S, Attström R, Hase J, Åström M, Movert R. Rinsing with delmopinol 0.2% and chlorhexidine 0.2%: short-term effect on salivary microbiology, plaque and gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1992;63:618-25.

- Moran J, Addy M, Wade WG, Maynard JH, Robert SE, Åström M, et al. A comparison of delmopinol and chlorhexidine on plaque regrowth over a 4-day period and salivary bacterial counts. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:749-53.

- Rundegren J, Hvid E, Johansson M, Åström M. Effect of 4 days mouth rinsing with delmopinol or chlorhexidine on the vitality of plaque bacteria. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:322-5.

- Eriksson B, Ottersgård Brorsson A-K, Hallström G, Sjödin T, Gunnarsson PO. Pharmacokinetics of 14C-delmopinol in the healthy male volunteer. Xenobiotica. 1998;28:1075-81.

- Sjödin T, Håkansson J, Sparre B, Ekman I, Åström M. Pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of delmopinol in an open rinse time study in healthy volunteers. Am J Dent. 2011;24:383-8.

- Eriksson B, Hallström G, Ottersgård Brorsson AK, Svensson L, Gunnarsson PO. Metabolic fate of delmopinol in man after mouth rinsing and after oral administration. Xenobiotica. 2000;30:179-92.

- Addy M, Moran J, Newcombe R. Meta-analyses of studies of 0.2% delmopinol mouth rinse as an adjunct to gingival health and plaque control measures. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:58-65.

- Claydon N, Hunter L, Moran J, Wade W, Kelty E, Movert R, et al. A 6-month home-usage trial of 0.1% and 0.2% delmopinol mouthwashes (I). Effects on plaque, gingivitis, supragingival calculus and tooth staining. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:220-8.

- Elworthy AJ, Edgar R, Moran J, Addy M, Movert R, Kelty E, et al. A 6-month home-usage trial of 0.1% and 0.2% delmopinol mouthwashes (II). Effects on the plaque microflora. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:527-32.

- Hase J, Attström R, Edwardsson S, Kelty E, Kisch J. 6-month use of 0.2% delmopinol hydrochloride in comparison with chlorhexidine digluconate and placebo (1). Effect on plaque formation and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:746-53.

- Hase J, Edwardsson S, Rundegren J, Attström R, Kelty E. 6-month use of 0.2% delmopinol hydrochloride in comparison with 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate and placebo (II). Effect on plaque and salivary microflora. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:841-9.

- Lang N, Hase J, Grassi M, Hämmerle CHF, Weigel C, Kelty E, et al. Plaque formation and gingivitis after supervised mouthrinsing with 0.2% delmopinol hydrochloride, 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate and placebo for 6 months. Oral Dis. 1998;4:105-13.

- Sjödin T, Diogo Löfgren C, Glantz PO, Christersson C. Delmopinol – adsorption to and absorption through the oral mucosa. Acta Odontol Scand. 2020;78(8):572-9.

- Bankvall M, Sjöberg F, Gale G, Wold A, Jontell M, Östman S. The oral microbiota of patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Microbiol. 2014;6:25739.

- Chakrabarty AK, Mraz S, Geisse JK, Anderson NJ. Aphthous ulcers associated with imiquimod and the treatment of actinic cheilitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:35-7.

- Porter SR, Hegarty A, Kaliakatsou F, Hodgson TA, Scully C. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:569-78.

- Edgar NR, Saleh D, Miller RA. Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis: A Review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2017;10(3):26-36.

- Queiroz SIML, Silva MVAD, Medeiros AMC, Oliveira PT, Gurgel BCV, Silveira ÉJDD. Recurrent aphthous ulceration: an epidemiological study of etiological factors, treatment and differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(3):341-6.

- Bartlett J, van der Voort Maarschalk K. Understanding the oral mucosal absorption and resulting clinical pharmacokinetics of asenapine. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2012;13:1110-15.

- Santos O, Lindh L, Halthur T, Arnebrant T. Adsorption from saliva to silica and hydroxyapatite surfaces and elution of salivary films by SDS and delmopinol. Biofouling. 2010;26(6):697-710.

- Svensson O, Halthur T, Sjödin T, Arnebrant T. The adsorption of delmopinol at the solid/liquid interface – The role of the acid-base equilibrium. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;350:275-81.

- Rushton, A. Safety of Hibitane II human experience II. J Clin Periodontol. 1977;4:73-9.

- Tarakji B, Gazal G, Al-Maweri SA, Azzeghaiby SN, Alaizari N. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis for dental practitioners. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7(5):74-80.

- Chavan M, Jain H, Diwan N, Khedkar S, Shete A, Durkar S. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41(8):577-83.

- Akintoye SO, Greenberg MS. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Dent Clin North Am. 2014;58(2):281-97.

Supplementary Tables

Baseline1) Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.0755; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.2348; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.1429; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.5867; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.7452; Del. 0.2 vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.4002 | ||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | ||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | |

DEC-89016 | 40 | 1 | 2.50 | 40 | 2 | 5.00 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-89017 | 39 | 3 | 7.69 | 44 | 2 | 4.55 | 38 | 1 | 2.63 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-90014 | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 50 | 0 | 0.00 |

DEC-90018 | 46 | 1 | 2.17 | 0 | 0 | · | 49 | 3 | 6.12 | 48 | 0 | 0.00 |

DEC-90019 | 157 | 2 | 1.27 | 157 | 0 | 0.00 | 156 | 2 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-91023 | 51 | 3 | 5.88 | 0 | 0 | · | 50 | 3 | 6.00 | 52 | 2 | 3.85 |

DEC-91025 | 150 | 0 | 0.00 | 150 | 2 | 1.33 | 150 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-91027 | 150 | 18 | 12.00 | 151 | 6 | 3.97 | 150 | 10 | 6.67 | 0 | 0 | · |

Total | 686 | 28 | 4.08 | 542 | 12 | 2.21 | 686 | 19 | 2.77 | 150 | 2 | 1.33 |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | ||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 1: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis at baseline.

4 – 6 weeks1) Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = >0.9999; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0151; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.6297; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0090; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.6323; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.0228 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 40 | 4 | 10.00 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 39 | 1 | 2.56 | 44 | 1 | 2.27 | 38 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90018 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90019 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 156 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91023 | 51 | 5 | 9.80 | 0 | 0 | · | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | 51 | 2 | 3.92 | |

DEC-91025 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | . | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 287 | 7 | 2.44 | 241 | 6 | 2.49 | 284 | 0 | 0.0 | 51 | 2 | 3.92 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 2: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 4-6 weeks of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are included.

2 – 3 months1) Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.0049; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0008; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.0080; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.8393; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.3181; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.4843 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 40 | 1 | 2.50 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 39 | 0 | 0.00 | 44 | 0 | 0.00 | 38 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-90018 | 46 | 3 | 6.52 | 0 | 0 | · | 49 | 1 | 2.04 | 48 | 1 | 2.08 | |

DEC-90019 | 157 | 0 | 0.00 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 156 | 1 | 0.64 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91023 | 48 | 6 | 12.50 | 0 | 0 | · | 48 | 2 | 4.17 | 49 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-91025 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 147 | 0 | 0.00 | 142 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 147 | 26 | 17.69 | 148 | 11 | 7.43 | 146 | 9 | 6.16 | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 677 | 37 | 5.47 | 536 | 12 | 2.24 | 672 | 13 | 1.93 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 3: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 2-3 months of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are included.

5 – 6 months 1) Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.1751; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.1418; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.7707; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = >0.9999; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.1021; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.1145 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 51 | 1 | 1.96 | 0 | 0 | · | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | 41 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-90018 | 43 | 3 | 6.98 | 0 | 0 | · | 48 | 0 | 0.00 | 42 | 1 | 2.38 | |

DEC-90019 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91023 | 47 | 4 | 8.51 | 0 | 0 | · | 47 | 3 | 6.38 | 47 | 4 | 8.51 | |

DEC-91025 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 142 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 288 | 9 | 3.13 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 287 | 3 | 1.05 | 130 | 5 | 3.85 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 4: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 5-6 months of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are included.

4 – 6 weeks 1) All patients with aphthous stomatitis at basline are excluded Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.7590; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0150; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.3440; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0442; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.2739; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.0221 | ||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | ||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | |

DEC-89016 | 39 | 0 | 0.00 | 38 | 2 | 5.26 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-89017 | 36 | 1 | 2.78 | 42 | 1 | 2.38 | 37 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-90014 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-90018 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-90019 | 154 | 1 | 0.65 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 154 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-91023 | 48 | 4 | 8.33 | 0 | 0 | · | 47 | 0 | 0.00 | 49 | 2 | 4.08 |

DEC-91025 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-91027 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · |

Total | 277 | 6 | 2.16 | 237 | 4 | 1.69 | 278 | 0 | 0.00 | 49 | 2 | 4.08 |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | ||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 5: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 4-6 weeks of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are not included.

2 – 3 months1) All patients with aphthous stomatitis at basline are excluded Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.0135; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0016; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.0435; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.8012; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.6920; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = >0.9999 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 39 | 1 | 2.56 | 38 | 0 | 0.00 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 36 | 0 | 0.00 | 42 | 0 | 0.00 | 37 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-90018 | 45 | 3 | 6.67 | 0 | 0 | · | 46 | 0 | 0.00 | 48 | 1 | 2.08 | |

DEC-90019 | 154 | 0 | 0.00 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 154 | 1 | 0.65 | 0 | 0 | . | |

DEC-91023 | 45 | 4 | 8.89 | 0 | 0 | · | 45 | 2 | 4.44 | 47 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-91025 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 145 | 0 | 0.00 | 142 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 129 | 17 | 13.18 | 142 | 7 | 4.93 | 136 | 5 | 3.68 | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 648 | 26 | 4.01 | 524 | 8 | 1.53 | 653 | 8 | 1.23 | 145 | 1 | 0.69 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 6: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 2-3 months of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are not included.

5 – 6 months1) All patients with aphthous stomatitis at basline are excluded Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.4314; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.5043; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.5131; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = >0.9999; Del. 0.1 vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.1924; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.2128 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 51 | 1 | 1.96 | 0 | 0 | · | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | 41 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-90018 | 42 | 2 | 4.76 | 0 | 0 | · | 45 | 0 | 0.00 | 42 | 1 | 2.38 | |

DEC-90019 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91023 | 44 | 2 | 4.55 | 0 | 0 | · | 47 | 3 | 6.38 | 47 | 3 | 6.38 | |

DEC-91025 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 145 | 1 | 0.69 | 142 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 284 | 6 | 2.11 | 145 | 1 | 0.69 | 284 | 3 | 1.06 | 130 | 4 | 3.08 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 7: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 5-6 months of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are not included.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication History

Received Date: 24-01-2022

Accepted Date: 11-02-2022

Published Date: 18-02-2022

Copyright© 2022 by Sjödin T, et al. All rights reserved. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: Sjödin T, et al. The Effect of Delmopinol Mouthwash on Aphthous Stomatitis. J Dental Health Oral Res. 2022;3(1):1-19.

Figure 1: Percentage of patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline and after for 4-6 weeks, 2-3 months and 5-6 months.

Figure 2: Percentage of patients without aphthous stomatitis at baseline and after 4-6 weeks, 2-3 months and 5-6 months.

Study Number | Number of Patients Entering Treatment | Treatment Length | Study Site | |||

Placebo | Delmopinol 0.1% | Delmopinol 0.2% | Chlorhexidine 0.2 % | |||

DEC-89016* | 40 | 40 | 40 | – | 8 weeks | Dep. of Periodontol, Inst. of Postgraduate Dental Education, Jönköping, Sweden |

DEC-89017* | 39 | 44 | 38 | – | 8 weeks | Dep. of Periodontol, University of Umeå, Sweden |

DEC-90014* | 53 | – | 53 | 50 | 6 months | Dep.of Periodontology, University of Bern, Switzerland |

DEC-90018* | 46 | – | 49 | 48 | 6 months | Dep. of Periodontolgy, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden |

DEC-90019 | 157 | 157 | 156 | – | 3 months | Dep. of Periodontol, University of Dublin, Ireland |

DEC-90023* | 51 | – | 50 | 52 | 5 months | School of Dental Medicine, University of Brussels, Belgium |

DEC-91025 | 150 | 150 | 150 | – | 6 months | University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff |

DEC-91027 | 150 | 151 | 150 | – | 3 months | Dep. of Periodontology, Faculty of Medicine, Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium |

Total number | 686 | 542 | 686 | 150 | ||

* The asterisk indicates that the rinsing in the study was supervised. | ||||||

Table 1: Number of patients and length of treatment in the phase III programme.

Supplementary Tables

Baseline1) Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.0755; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.2348; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.1429; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.5867; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.7452; Del. 0.2 vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.4002 | ||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | ||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | |

DEC-89016 | 40 | 1 | 2.50 | 40 | 2 | 5.00 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-89017 | 39 | 3 | 7.69 | 44 | 2 | 4.55 | 38 | 1 | 2.63 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-90014 | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 50 | 0 | 0.00 |

DEC-90018 | 46 | 1 | 2.17 | 0 | 0 | · | 49 | 3 | 6.12 | 48 | 0 | 0.00 |

DEC-90019 | 157 | 2 | 1.27 | 157 | 0 | 0.00 | 156 | 2 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-91023 | 51 | 3 | 5.88 | 0 | 0 | · | 50 | 3 | 6.00 | 52 | 2 | 3.85 |

DEC-91025 | 150 | 0 | 0.00 | 150 | 2 | 1.33 | 150 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-91027 | 150 | 18 | 12.00 | 151 | 6 | 3.97 | 150 | 10 | 6.67 | 0 | 0 | · |

Total | 686 | 28 | 4.08 | 542 | 12 | 2.21 | 686 | 19 | 2.77 | 150 | 2 | 1.33 |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | ||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 1: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis at baseline.

4 – 6 weeks1) Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = >0.9999; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0151; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.6297; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0090; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.6323; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.0228 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 40 | 4 | 10.00 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 39 | 1 | 2.56 | 44 | 1 | 2.27 | 38 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90018 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90019 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 156 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91023 | 51 | 5 | 9.80 | 0 | 0 | · | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | 51 | 2 | 3.92 | |

DEC-91025 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | . | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 287 | 7 | 2.44 | 241 | 6 | 2.49 | 284 | 0 | 0.0 | 51 | 2 | 3.92 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 2: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 4-6 weeks of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are included.

2 – 3 months1) Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.0049; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0008; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.0080; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.8393; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.3181; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.4843 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 40 | 1 | 2.50 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 39 | 0 | 0.00 | 44 | 0 | 0.00 | 38 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-90018 | 46 | 3 | 6.52 | 0 | 0 | · | 49 | 1 | 2.04 | 48 | 1 | 2.08 | |

DEC-90019 | 157 | 0 | 0.00 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 156 | 1 | 0.64 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91023 | 48 | 6 | 12.50 | 0 | 0 | · | 48 | 2 | 4.17 | 49 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-91025 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 147 | 0 | 0.00 | 142 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 147 | 26 | 17.69 | 148 | 11 | 7.43 | 146 | 9 | 6.16 | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 677 | 37 | 5.47 | 536 | 12 | 2.24 | 672 | 13 | 1.93 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 3: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 2-3 months of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are included.

5 – 6 months 1) Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.1751; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.1418; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.7707; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = >0.9999; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.1021; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.1145 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 51 | 1 | 1.96 | 0 | 0 | · | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | 41 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-90018 | 43 | 3 | 6.98 | 0 | 0 | · | 48 | 0 | 0.00 | 42 | 1 | 2.38 | |

DEC-90019 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91023 | 47 | 4 | 8.51 | 0 | 0 | · | 47 | 3 | 6.38 | 47 | 4 | 8.51 | |

DEC-91025 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 142 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 288 | 9 | 3.13 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 287 | 3 | 1.05 | 130 | 5 | 3.85 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 4: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 5-6 months of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are included.

4 – 6 weeks 1) All patients with aphthous stomatitis at basline are excluded Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.7590; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0150; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.3440; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0442; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.2739; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.0221 | ||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | ||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | |

DEC-89016 | 39 | 0 | 0.00 | 38 | 2 | 5.26 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-89017 | 36 | 1 | 2.78 | 42 | 1 | 2.38 | 37 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-90014 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-90018 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-90019 | 154 | 1 | 0.65 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 154 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-91023 | 48 | 4 | 8.33 | 0 | 0 | · | 47 | 0 | 0.00 | 49 | 2 | 4.08 |

DEC-91025 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · |

DEC-91027 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · |

Total | 277 | 6 | 2.16 | 237 | 4 | 1.69 | 278 | 0 | 0.00 | 49 | 2 | 4.08 |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | ||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 5: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 4-6 weeks of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are not included.

2 – 3 months1) All patients with aphthous stomatitis at basline are excluded Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.0135; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.0016; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.0435; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.8012; Del. 0.1% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.6920; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = >0.9999 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 39 | 1 | 2.56 | 38 | 0 | 0.00 | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 36 | 0 | 0.00 | 42 | 0 | 0.00 | 37 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | 53 | 0 | 0.00 | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-90018 | 45 | 3 | 6.67 | 0 | 0 | · | 46 | 0 | 0.00 | 48 | 1 | 2.08 | |

DEC-90019 | 154 | 0 | 0.00 | 157 | 1 | 0.64 | 154 | 1 | 0.65 | 0 | 0 | . | |

DEC-91023 | 45 | 4 | 8.89 | 0 | 0 | · | 45 | 2 | 4.44 | 47 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-91025 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 145 | 0 | 0.00 | 142 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 129 | 17 | 13.18 | 142 | 7 | 4.93 | 136 | 5 | 3.68 | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 648 | 26 | 4.01 | 524 | 8 | 1.53 | 653 | 8 | 1.23 | 145 | 1 | 0.69 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 6: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 2-3 months of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are not included.

5 – 6 months1) All patients with aphthous stomatitis at basline are excluded Placebo vs Del. 0.1%: p = 0.4314; Placebo vs Del. 0.2%: p = 0.5043; Placebo vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.5131; Del. 0.1% vs Del. 0.2%: p = >0.9999; Del. 0.1 vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.1924; Del. 0.2% vs Chlx 0.2%: p = 0.2128 | |||||||||||||

Study No. | Placebo | Del. 0.1% | Del. 0.2% | Chlx 0.2% | |||||||||

n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | n | # | % | ||

DEC-89016 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-89017 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-90014 | 51 | 1 | 1.96 | 0 | 0 | · | 50 | 0 | 0.00 | 41 | 0 | 0.00 | |

DEC-90018 | 42 | 2 | 4.76 | 0 | 0 | · | 45 | 0 | 0.00 | 42 | 1 | 2.38 | |

DEC-90019 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91023 | 44 | 2 | 4.55 | 0 | 0 | · | 47 | 3 | 6.38 | 47 | 3 | 6.38 | |

DEC-91025 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | 145 | 1 | 0.69 | 142 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | · | |

DEC-91027 | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | 0 | 0 | · | |

Total | 284 | 6 | 2.11 | 145 | 1 | 0.69 | 284 | 3 | 1.06 | 130 | 4 | 3.08 | |

P-values calculated using the Fisher´s exact test. 2-sided p-values are presented. | |||||||||||||

Supplemental Table 7: Number of patients with Adverse Events (AE) reported as aphthous stomatitis after 5-6 months of treatment. Patients with aphthous stomatitis at baseline are not included.